Leaders should spend time on the shop floor every day, communicating with customers and employees and helping to drive operational excellence. Too many executives lack the skills or motivation to do so.

“A desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world,” read a sign on the wall of Lou Gerstner’s office. During his time as CEO of IBM, Gerstner flew more than a million miles to meet customers, employees and business partners1 . Our own research shows that performance transformations are 2.6 times more likely to succeed if they have strong involvement from the top of the organization2 . But we also know from experience that few senior leaders are as visible or active on the frontline as Gerstner was.

In Japanese police dramas the gemba is “the real place”: the scene of the crime. In modern management, the phrase has come to mean the place where value is created or client-facing interactions take place: the factory, call center or shop floor. More specifically, the term is often used to describe the need to spend regular time at the organization’s frontline “managing by walking about.” In the best lean companies, all executives, from CEO to front-line team leaders, spend at least an hour on the shop floor every day.

These gemba walks serve a range of useful purposes. They drive continuous improvement by helping managers and their teams spot waste and quality risks, identify improvement opportunities or find the root cause of issues. In sales environments, they help managers to gain first-hand insights into real customer needs, concerns and behaviors. They help to build the right capabilities and mindsets, giving managers the chance to be visible role models, and the opportunity to provide direct coaching and support to front-line personnel. And they help build a strong culture by enabling clear, direct communication between different levels of the organization. Larry Bossidy, former chairman and CEO of AlliedSignal and former chairman of Honeywell, notes that “many people regard execution as detail work that’s beneath the dignity of a business leader. That’s wrong . . . it’s a leader’s most important job.”3 Time and time again, gemba walks are mentioned as a key success factor by lean practitioners.

Despite these compelling benefits, regular gemba walks are something that many executives find surprisingly difficult to do. Analysis of the way middle managers spent their time in one financial services business, for example, revealed that they spent less than 10 percent of their time on the shop floor, even though that shop floor environment was a call center located right next to their office. For senior executives in the same company the typical weekly shop floor time was zero hours. In manufacturing businesses, where the shop floor may be distant, noisy or require special clothing to enter, management appearances can be even rarer than that. One school principal even told us that his teachers would find his presence in the classroom disturbing.

When we interview executives about their reasons for not visiting the shop floor, some common excuses emerge. Shortage of time is one, with some managers thinking that time on the shop floor will be time wasted, or that they simply won’t be able to find anything useful on their shop floor visits. Other managers worry about appearing to short-circuit the natural chain of command by appearing to go over the heads of their direct reports. If we press a little harder, some managers admit to being concerned about being put on the spot and having their limited knowledge of key equipment or processes revealed, while others fear being asked questions by front-line staff they will not be able to answer.

In some businesses, by contrast, we see a different kind of problem. Bricks and mortar retailers, for example, often have a strong culture of management visibility on the shop floor. But while they are there, managers may spend their time on activities—like tidying shelves, or cajoling front-line staff to work faster—that don’t contribute to sustainable, long-term performance improvement.

Fortunately for executives and their front-line teams, overcoming these barriers to effective gemba walks is quite possible with a few practical tips and tricks.

Making room to walk

The first step for any manager looking to master the gemba walk is removal of the barriers that keep them from the shop floor in the first place. This is a scheduling problem: if managers start treating gemba walks the same way they treat meetings or conference calls—by allocating a fixed time in their daily agenda and sticking to it—they can help to ensure other events don’t get in the way. Site or company-wide policies can help too, like not scheduling other meetings before 11:00 AM to leave free time for gemba walks, for example, or monitoring schedule compliance as a performance indicator for managers.

A second step is for managers to overcome concerns they have about upsetting the people who report to them. This calls for communication: talk to your direct report, explain that the purpose of the gemba walk is not to check up on or bypass them, but an opportunity to provide additional support, accelerate problem solving, and improve your own knowledge of front-line operations, allowing you to make better-informed decisions. Reinforce these messages after each walk by discussing your observations and experiences with your staff.

A conversation with direct reports can also help managers address some of their own concerns about shop floor interactions. For example, these conversations can identify issues that are causing concern on the frontline, ensuring that “difficult” questions from front-line staff do not come as a surprise. It isn’t necessary to be able to provide an answer to every question that front-line teams might pose, but prior knowledge of likely topics will at least help managers to come up with an appropriate response.

Making walks effective

The key to ensuring that gemba walks deliver value for the time spent lies in having an explicit goal for each walk. Such goals might include checking the current performance of an asset before making investment decisions, assessing the performance of a new associate, reinforcing communication about a new company policy, or investigating possible causes of quality complaints. Some managers find it useful to use a menu of gemba walk strategies (see menu at end) from which they can pick the most appropriate strategy for a given day and part of the shop floor. Let’s illustrate this technique with a typical example.

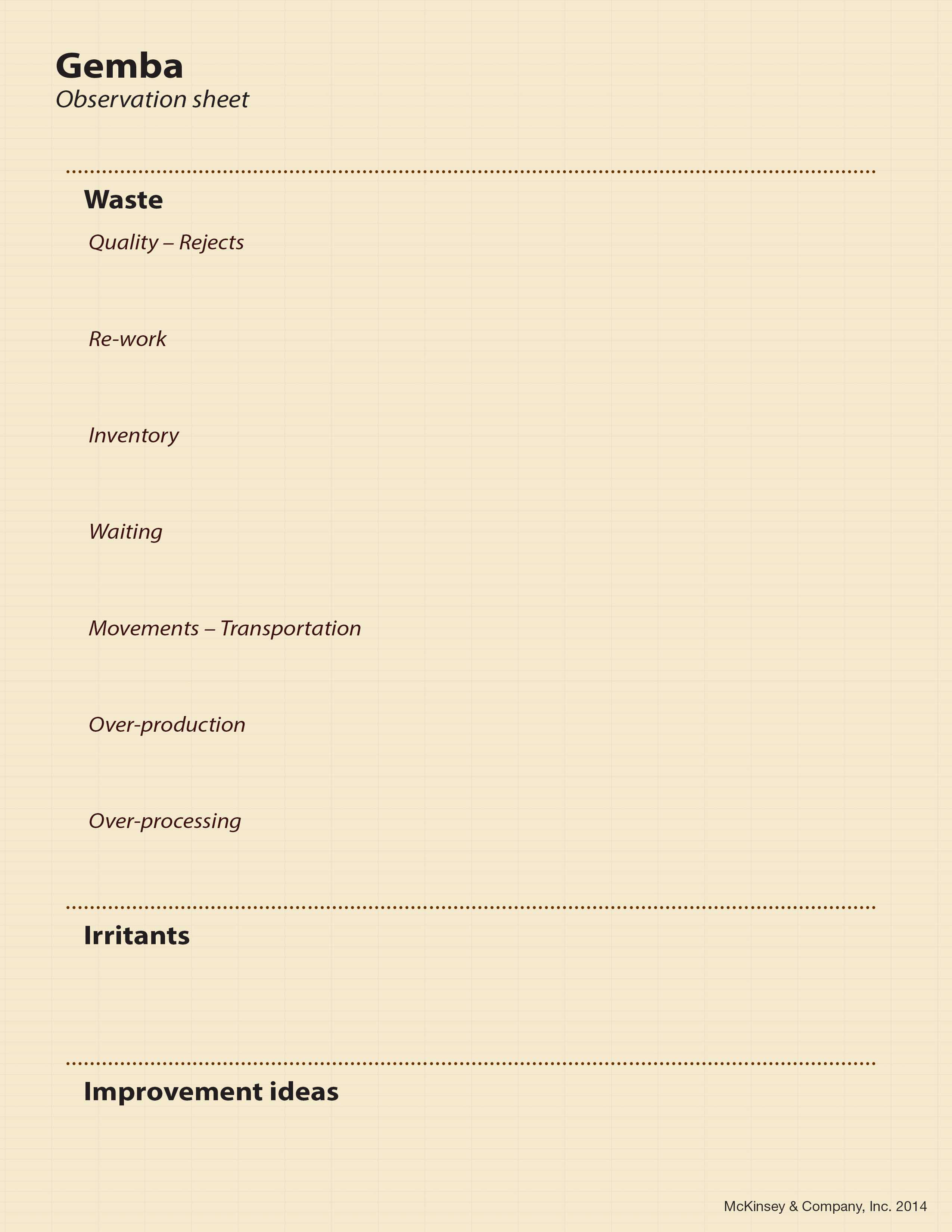

If she decided it was appropriate to observe a task and identify improvement ideas with its operator, the manager would prepare for the walk by informing the operator during the daily pre-shift briefing that this will be their intention, and by reviewing the written standard operating procedure (SOP) for the task. It can also be useful to have a pre-prepared template, such as one outlining the eight forms of waste (see observation sheet at end), or a process confirmation sheet describing the critical aspects of the task that should be checked, to use as a note-taking and idea generation aid.

At the workstation, the manager will remind the operator of the purpose of the exercise before beginning to make observations and take notes. There is no need for the manager to have a comprehensive understanding of the task—just ask the operator to explain any aspects that are not clear or understood. Open questions (e.g., ”What are you doing now?”; “Why are you doing that?”; or “What would you do differently to save time, or improve quality?”) allow the operator to explain the task as they understand it, and can give important hints about irritants or possible improvements.

At the end of the observation period, the manager will discuss her observations and thoughts with the operator, and ask if they agree with any irritants or wastes identified, if they have any ideas for dealing with them, and if there are any actions that can be taken straight away to address those issues.

A gemba walk only adds value if some actions are taken as a result. After the walk, therefore, it is important that ideas or improvement opportunities are followed up. Typically, the manager will give feedback on their observations and ideas at the next daily or weekly meeting, and add appropriate actions to the on-going improvements list. The best managers ensure they give themselves personal responsibility for some of the identified actions, and that they act as effective role models by sticking to those commitments.

Tips for success

Most managers find that, regardless of their initial trepidation, repetition quickly makes gemba walks both easier and more effective. Our experience helping managers at all levels and across a range of industries to develop their gemba skills has taught us some valuable additional lessons:

- Take a walk with an expert. Most executives find taking a walk on their own shop floor with performance improvement specialists, from their own organization or outside it, can be an attitude-changing experience. The sheer number of opportunities for improvement that are immediately apparent to the practiced eye usually comes as a surprise to even the most seasoned executive.

- Get some training in the basics. Deep expertise in gemba walks comes with experience, but executives can give themselves a head start with some formal training in skills like spotting wastes, running problem-solving sessions or giving constructive feedback. Companies often find it useful to institutionalize such training for executives, supported by coaching from experts, as they begin to practice what they have learned.

- Go and see everywhere. There may be a strong temptation, particularly for managers operating close to the frontline, to concentrate time and energy on areas with the most significant issues. They should do this by all means, but not at the expense of higher performing areas, which will still have the same need for communication, process confirmation and reward for good performance.

- Ask simple questions. A new eye can often uncover substantial improvement opportunities by challenging habits that have become so ingrained that nobody at the frontline has thought to question them. Simple questions can reinforce key cultural points too. At Emerson Electric, CEO David Farr makes a point of asking virtually everyone he encounters the same four questions: “How do you make a difference?”; “What improvement ideas are you working on?”; “When did you last get coaching from your boss?”; and “Who is the enemy?”.4

- Small things matter. Comparatively simple problems, like unreliable printers or a shortage of cleaning equipment, can become huge frustrations for staff that must confront them on a daily basis. Swift action to fix these issues is a powerful morale booster and sends a clear signal to staff that they are being heard, encouraging them to discuss other concerns or improvement ideas.

- Build your skills. Some types of gemba walk are harder than others. Managers often find it useful to build their own confidence and those of their front-line staff by beginning with simpler objectives, like observing processes or coaching employees on a new task. In themselves, these activities will reveal a lot about the realities of front-line operations, providing invaluable background for more complex tasks, like problem solving sessions, or difficult ones, like coaching staff who aren’t complying with process standards.

The long walk to lean

Once they have picked up the habit of regular, effective gemba walks, few executives could imagine life without them. Time in the gemba becomes an integral part of their communication, performance management and continuous improvement strategies.

In most cases, front-line performance is transformed as result of small, but frequent and regular interactions on the shop floor, but it can be surprisingly common for a single walk to deliver significant impact. Take the case of one pharmaceutical company that introduced a gemba walk program for its entire senior management team. In one such walk a commercial manager accompanied some of his operations colleagues onto the manufacturing floor. Their objective was problem-solving a printing machine on a liquids packaging line. Operators were struggling to get a printed logo to align properly on vials of vaccine, and setting up new batches was a frustratingly slow process. Watching the work, the commercial manager asked why the company was trying to print the logo at all on a product that was always supplied in secondary packaging, and which had no influence on purchasing or use decisions. That single comment allowed the company to simplify its labels, increasing output on the line by at least 10 percent.

What similar opportunities await you on your shop floor? Shouldn’t you take a gemba walk to find out?

Gemba menu

Gemba Observation sheet