As the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic comes into sharper focus, the position of the nation’s small businesses appears, overall, to be particularly bleak.1 By mid-April, according to a report from the Facebook & Small Business Roundtable, about a third had temporarily stopped operating,2 and by mid-May more than half had laid off or furloughed employees. Our analysis of several surveys of small businesses suggests that before accounting for intervention, 1.4 million to 2.1 million of them (25 to 36 percent) could close permanently as a result of the disruption from just the first four months of the COVID-19 pandemic.3

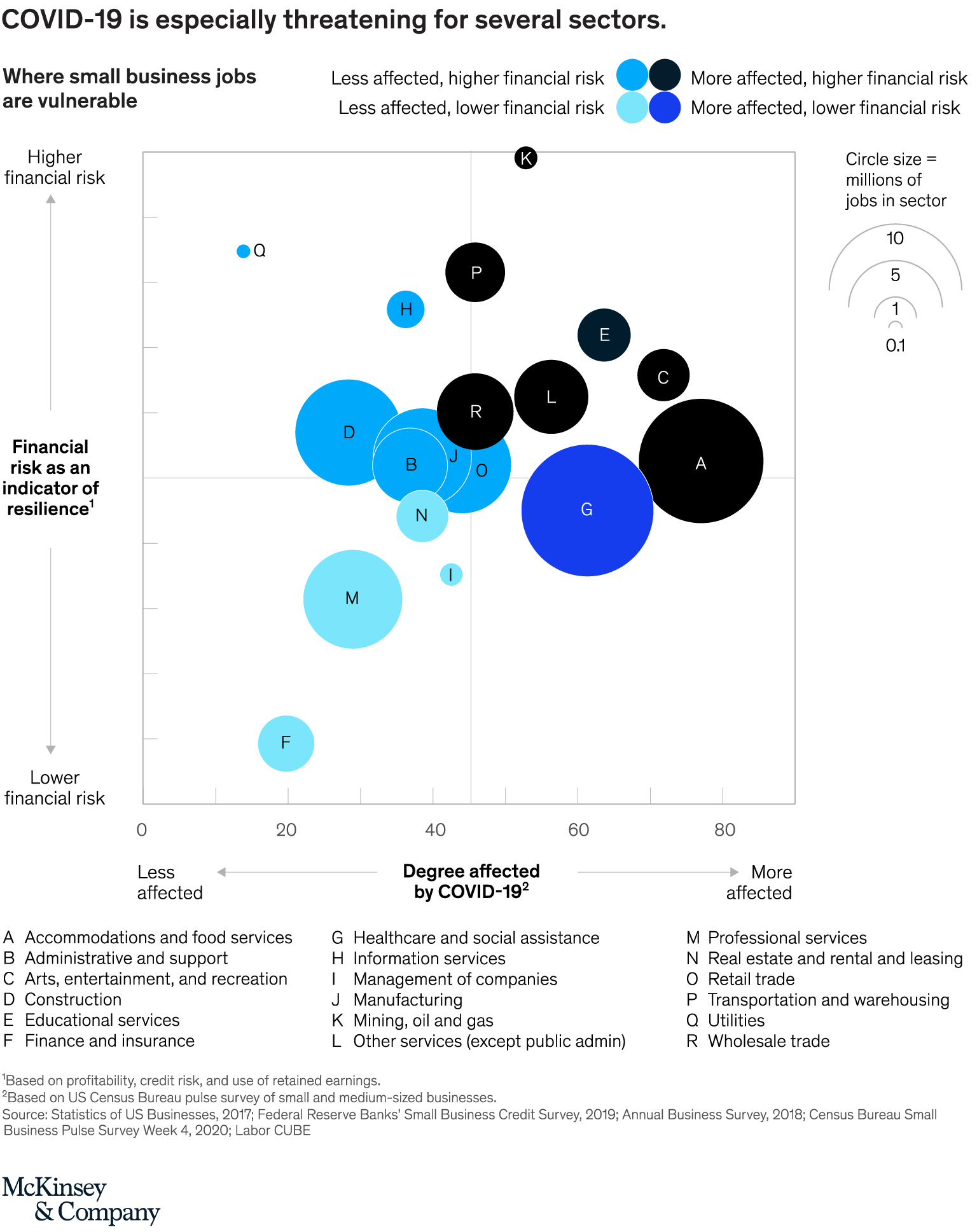

Some small businesses may close because they’re in industries, such as accommodations, food service, and educational services, that are affected by changed customer behavior, especially the physical distancing and mandated operational restrictions that began during the pandemic. Other small businesses may close because they were already at risk financially before the crisis. Indeed, recent research by the Federal Reserve4 finds that only 35 percent of small businesses were healthy at the end of 2019 and that less healthy ones were three times more likely than the others to close or sell in response to a revenue shock (see sidebar, “Our methodology”). The most vulnerable small businesses face both financial and COVID-related challenges (Exhibit 1).

Before the crisis, small businesses accounted for nearly half of all private-sector jobs. Widespread business exits wreak longer-lasting unemployment and economic damage than temporary shutdowns do, so it’s important to understand which small businesses may remain shuttered permanently. That knowledge can help business leaders and policy makers develop interventions to protect small businesses in the short term, ensure that they can participate in the recovery, and put more of them on a more resilient footing in the years to come.

Sectors most at risk

Plotting the effects of COVID-19 against existing financial risk sheds light on the overall vulnerability of small businesses. The sectors most affected by the coronavirus and the least financially resilient include 1.7 million small businesses, employ 20 million workers, and earn 12 percent of US business revenue (Exhibit 2). A long-lasting COVID-19 crisis could continue to affect these sectors disproportionately and make more of their firms vulnerable to permanent closure.

The potential fallout from the pandemic goes deeper the longer it plays out. An additional two million small businesses compete in sectors, such as construction and manufacturing, which have fewer businesses that now report negative effects from the pandemic but are also less financially resilient. The longer the economic impact from COVID- 19 continues, the more risk these sectors face. Construction, for example, is believed to be highly sensitive to the economy’s overall health, so a more protracted recovery, combined with relatively low resilience, could lead to significant vulnerability later.

Measuring the vulnerability of US small businesses during the COVID-19 crisis

Determining each sector’s level of immediate vulnerability provides a clearer view of the magnitude of the challenge small businesses face in the first few months of the crisis. Surveys of small-business owners helped us generate a range of estimates. At the low end, half of small businesses experiencing a “large negative effect” from COVID-19 could become vulnerable to closure, according to these owners. At the high end, an additional quarter of small businesses, experiencing a “moderate negative effect,” could become vulnerable to closure.

Differences between sectors depend on how much COVID-19 has affected them and how likely affected businesses are to close (Exhibit 3). It isn’t only the kinds of small businesses with well-known challenges, such as restaurants and hotels, that are greatly affected. So are other small businesses, in educational services, healthcare, and social assistance. Many private-sector educational services, childhood-education centers, sports classes, and art schools, where physical distancing would be a challenge, could become vulnerable. Similarly, small businesses in the healthcare sector—including ambulatory care (such as dentists’ offices) and small private practices that patients may be reluctant to visit in person—are also highly affected.

Both public-health regulations and changed consumer behavior can shape the vulnerability of subsectors in the same broader industry differently.

Within retail, for example, three-quarters of clothing stores reported a large negative impact on their business as of May 23rd, but only a third of food and beverage stores did. This disparity probably reflects differences in which businesses were classified as essential and therefore allowed to continue operating. In other sectors, short-term lapses in demand may affect differences among subsectors. Within manufacturing, apparel manufacturers, given the pandemic’s impact on the retailing of clothes, are among the hardest-hit small businesses: 71 percent report a large negative impact. Among the electric-equipment and -appliance manufacturers, though, only a fifth report a large negative impact. A similar pattern emerged for financial resilience when we used a data set of financial statements within manufacturing subsectors: before COVID-19, apparel manufacturers had a lower ratio of cash on hand to current liabilities than computer and electronics manufacturers did.

Greater risk for certain business owners

The differences in vulnerability across sectors also create a disproportionate level of risk for lower-income workers, minority business owners, and business owners with less educational attainment. The most vulnerable sectors have the lowest average median income among the four quadrants, at around $13,000, or a third lower than the average median income in the other three (Exhibit 4).

In addition, minorities own a quarter of small businesses in the most affected sectors, compared with around 15 percent in the less affected ones. We considered only the effects of sector mix, but other research has found that minority-owned businesses are also particularly at risk because they tend to have lower resilience. Business owners with only a high-school degree or less are disproportionately at risk as well, since their businesses tend to be in less resilient sectors, particularly in construction and in services (such as repairs, maintenance, and laundry services) in which a third or more of the business owners had, at most, a high-school diploma.

Coronavirus: Leading through the crisis

Owners of the smallest firms are also particularly vulnerable. After analyzing previous recessions,5 when these firms accounted for the vast majority of permanent closures, we estimate that without effective interventions, around a quarter to around 40 percent of small businesses with fewer than 20 employees could be vulnerable to closing permanently in the first four months of the COVID-19 crisis, compared with less than 5 percent of firms with 100 to 499 employees. However, those larger firms could significantly reduce their employment levels or shutter many locations, even if they do not close permanently as a whole.

Geographic differences in vulnerability

Some of the states with the largest outbreaks, such as Michigan, New Jersey, and New York, also have the highest percentage of vulnerable small businesses (Exhibit 5), likely because of their stricter shelter-in-place rules.6 Alaska’s high percentage of vulnerable businesses shows the role of the sector mix. COVID-19 has affected the state to a more than average extent, and Alaska has a higher share of businesses in the most vulnerable sectors, particularly accommodations, food service, transportation, and warehousing.

The case for support

Protecting small businesses from widespread permanent closure is important because of the many roles they play in the economy, as employers, engines of entrepreneurship, economic multipliers, and community hubs.

- Small businesses as employers. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, small businesses accounted for half of private-sector jobs and for two-thirds of net new jobs created from 2000 to 2017. Permanent closures of small businesses are thought to generate longer-lasting unemployment than temporary furloughs and layoffs do. Even as the economy started to recover, current employees would need to seek jobs at different employers, potentially reducing their earnings. Studies of previous recessions show that people who lost their jobs earned 17.5 percent less at their new ones,7 which could be of particular concern for women, since pressure on wages could disproportionately make them drop out of the workforce.

- Entrepreneurship engines. Small businesses create unique entrepreneurial opportunities, particularly for women, minorities, and immigrants. Families that own businesses tend to be more upwardly mobile than those employed by others.8 Widespread, permanent exits of small businesses could also eliminate the physical capital and investments that went into them—everything from restaurant tables and decorations to the machinery at small factories.

- Economic multipliers. Many larger firms rely on small businesses as suppliers, direct customers for B2B services, or employers for many of their customers. Very small businesses often form a significant percentage of industries, such as real estate and information services, that have high employment multipliers, so job losses in these industries could cause significant job losses in the broader economy. Widespread exits of small businesses could disrupt the larger firms that rely on them and have knock-on effects for employment by reducing spending in the economy. Disturbingly, in previous recessions the percentage of small businesses and of businesses owned by minorities or women in some supply chains fell by 25 percent.

- Community hubs. Small businesses still form the backbone of many communities: for example, according to one industry organization, more than nine in ten Americans shop at a small business every month. This is particularly important for smaller communities, where small businesses form a larger proportion of overall income. Since the beginning of the crisis, several anecdotes have highlighted the social challenges for small towns that lose small businesses and the ripple effects on these communities.9

Implications for business and government leaders

The ultimate path of the crisis will depend on public-health and economic-policy responses. But ongoing interventions are needed not just to give small businesses immediate relief but also to sustain recovery by building longer-term resilience. The economy may continue to operate at a reduced capacity, with operating restrictions on small businesses, until a vaccine is available. Such scenarios, discussed at greater length in McKinsey’s broader economic research, could indicate that small businesses may need support over the length of the crisis.

Firms in sectors now strongly affected by COVID-19 will probably need relief interventions that focus on improving revenues and reducing costs. But less resilient small businesses may be unlikely to benefit from programs that require strong existing banking relationships,10 so they may need new or special forms of credit. Even in more resilient sectors, ensuring access to capital for less resilient small businesses could also help level the playing field, particularly for those owned by minorities.

Business leaders, policy makers, and concerned people generally can all do their part to support small businesses during the crisis. For business leaders the possibilities include these:

- Prioritizing small businesses in procurement, particularly by locking in demand for several years. Such actions can also promote access to credit, particularly in manufacturing. Long-term purchase commitments to small businesses that supply larger ones would give financial institutions more confidence to lend now.

- Paying receivables to small businesses ahead of schedule. This would be particularly helpful for highly affected small businesses that need immediate operating revenues. Instead of 90-day terms, 30-day terms or even payment upon receipt of invoices could be extremely helpful to improve the cash flow of small businesses.

- Crafting special kinds of support for small businesses that tend to have lower resilience. This move would be particularly relevant for larger financial institutions, which can commit themselves to lend more to less resilient sectors, to businesses owned by women or minorities, and to the smallest businesses. Under the status quo, it is a challenge for financial institutions to make loans to less resilient businesses, yet such institutions might reap benefits if they did. Proactively engaging with less resilient clients and considering relaxed payment schedules and credit availability during the crisis could, for example, deepen customer relationships in the future.

Governments could consider the following moves to support small businesses in the relief phase and the longer term:

- providing sector-specific support, such as helping to supply personal protective equipment in bulk to customer-facing industries, as small businesses reopen

- establishing local portals like those in Houston and Oakland to help customers support small businesses that are operating; some cities, such as Boston and Honolulu, have also created portals of programs to cover the expenses of implementing physical distancing

- working with private financial institutions to improve access to credit or developing additional emergency grants, loans, and incentives to help businesses with lower financial resilience

- promoting structural reforms that encourage financial institutions to provide longer-term access to capital and create incentives for small businesses to upgrade their facilities and digitize; such reforms could also support the business owners’ capabilities (including business planning, market identification, and technical assistance) and investments in worker training

People in general can also support small businesses:

- shopping at them wherever possible instead of larger, more resilient ones

- buying from larger companies, when possible, that have programs to support their small-business suppliers and customers

COVID-19 has been a significant economic challenge to millions of small businesses in the United States. It could threaten many more, particularly those with less resilience. Business leaders and governments that support these businesses can help them continue operating and put them on a more sustainable, resilient footing, so they can continue to anchor communities by supporting local economies.