ReNew Power is just ten years old—but a lot can happen in a decade. Today, ReNew is India’s largest renewable-energy company, with more than 110 wind and solar sites across the country. Backed by a group of prominent global investors, ReNew now generates 1 percent of India’s total electricity. Founder, chairman, and managing director Sumant Sinha has championed entrepreneurship by women, whose increased participation in the workforce could boost India’s GDP. ReNew has spurred the creation of nearly 85,000 jobs since 2011, and the company is heeding the government’s call for India to become self-sufficient; in July of last year, ReNew announced plans to manufacture solar cells and modules in India.

While coal is expected to remain a significant component of the country’s energy mix for several decades, India is placing big bets on renewable power, which could make up nearly half of global total electricity capacity by 2035. The stakes are high: decarbonizing the global power sector, which accounts for about one-third of the world’s carbon emissions, would be critical to preventing the worst effects of climate change. As Sinha puts it, “As fast as we might go, it won’t be anywhere near fast enough.”

India’s energy needs are growing, and McKinsey projects that the country’s energy demand will roughly double by 2050. The government aims to get 40 percent of its total energy capacity from renewable energy by 2030, up from 24 percent now.

ReNew is helping to address this deficit. Sinha sees Asia transforming at the speed of light: the power industry is being remade, mobility is morphing, and digitalization will have profound and perhaps unforeseeable consequences for the continent. He reflected on the future of Asia in a discussion with McKinsey’s Amit Khera and Jason Li.

The Quarterly: What sets Asian companies apart? What are their most distinctive qualities?

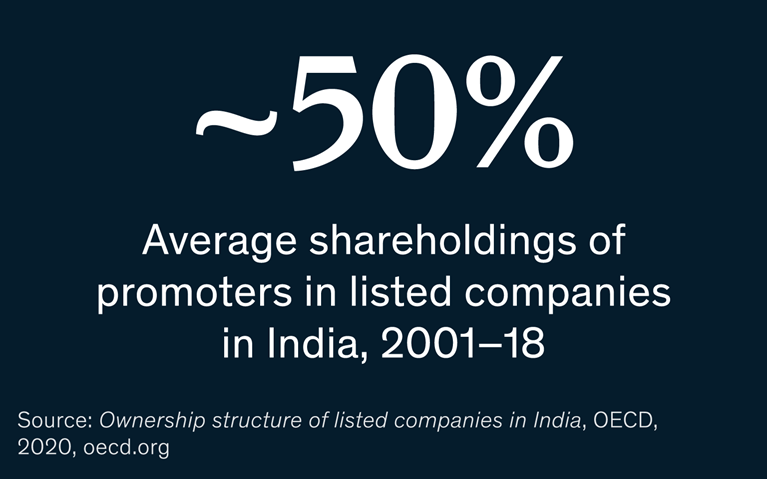

Sumant Sinha: Indian companies—and Asian companies overall—are more family-driven than companies in the West. Most Indian companies have a predominant shareholder, or promoter.1 The motivations of these individuals differ from those of institutional shareholders, which are the primary owners of companies in the Western world.

There are advantages and disadvantages to this. Promoters tend to have a much longer-term mindset; they tend to think much more about the future than a management team might if it was driven by short-term results and incentives. On the flip side, sometimes promoters looking to protect their shareholding are unwilling to raise capital, even when it might be the right move for the company.

In general, companies in Asia, and perhaps more so in India, haven’t yet fully matured as board-run companies. Today, there are few non-promoter-driven companies in India, but this could change very quickly in the coming years as more Indian unicorns emerge.

The Quarterly: How does the general Indian culture affect corporate culture?

Sumant Sinha: Indian society is a little bit more hierarchical—less aggressive and more hidebound. To some extent, I think that reduces the level of innovation, free thinking, and meritocracy. How many young Indian CEOs can you think of? In the West, you see CEOs of major companies in their early 40s given a long run.

Indian companies do much less R&D. We don’t invest much in finding new or better ways of doing things. Indian companies are very good at translating existing technologies into viable domestic business models with lower costs. Only rarely do you see business-model or manufacturing innovations. That’s reflected in the lack of industry–academia collaborations, and in the number of patents that come out of India.

The Quarterly: Our research suggests that India has one of the largest opportunities in the world to boost GDP by advancing women’s equality.

Sumant Sinha: Unfortunately, traditional gender roles remain entrenched in India, and more so in the energy sector. However, at ReNew, we are committed to hiring women, particularly at the middle- and senior-management levels. We’ve launched several initiatives, such as “Power of W,” a women-only group where women are encouraged to speak up and share their inspiring stories; women’s mentoring programs; and various learning sessions aimed at promoting women’s workforce participation and economic independence. We also ensure that men are included, and that they, in fact, even champion some of these women’s empowerment programs so that they can be part of the solution rather than just being told what to do.

I feel a personal responsibility to advance gender equality, but this is not just about doing the right thing. India will not realize its growth potential without achieving gender equality, including in the workplace.

India will not realize its growth potential without achieving gender equality, including in the workplace.

The Quarterly: How do you see Asia changing in the coming years? What are the most important changes you see happening across the region?

Sumant Sinha: A massive transition is currently underway in energy and, more specifically, electricity. In the large markets that are leading this transition, there will be a total inversion in how electricity is generated over the next ten to 15 years.

In India, two-thirds of electricity is currently generated using coal. The country’s electricity use is set to double, and two-thirds of that additional capacity will come from renewable sources. Driving that change will be a massive opportunity.

The changes on the horizon for the power sector go beyond the shift toward renewables. Most of the distribution utilities in India are owned by the government. For better or worse, I believe that the entire sector will ultimately be privatized. This will drive significant improvements; companies will be able to get closer to end customers.

Fundamental changes in mobility will also affect the power sector. Ridesharing companies and other transportation will move toward electric mobility. The national railway plans to transition all of its electricity procurement to solar and other green sources, using all available land, including beside the railway tracks. Can you imagine? Every railway line in India will have solar panels installed next to it.

Everything about how we generate, transmit, and consume power is about to radically change. India consumes about 1.5 trillion kilowatt-hours of electricity per year, which is about $100 billion to $120 billion; at most, it’s about 4 to 5 percent of total GDP. But when profit pools begin to appear on the distribution side, the impact will be profound.

The Quarterly: What underlies this massive shift in such a traditional sector?

Sumant Sinha: Two key factors drive this change. Immense technological changes are driving the shift from coal to renewables. Renewable energy is a young industry, and so far most of the players have been new companies like ours that are working hard to scale up. The traditional energy companies are beginning to adopt new technologies, and eventually there will be a tsunami of companies entering the industry.

Perhaps even more important, the increased awareness about climate change and carbon emissions has put significant pressure on the power sector. That pressure is being magnified in all kinds of ways: through civil society, the financial community, and governments—as well as corporate buyers of power.

Why do you think companies like Tesla are trading at around a $700 billion market cap? That’s more than the next five largest auto companies in the world put together. The financial markets are waking up to the issue of climate change, and valuations in the renewable-energy industry will begin to change considerably.

The Quarterly: What sorts of challenges is ReNew facing?

Sumant Sinha: The climate action imperative is enough to drive our business forward. The constraints are in our ability to execute more projects on the ground and our ability to access more capital to fund all of those projects. Even if tomorrow the world said, “We need ten times the amount of renewable energy that we have today,” the problem is that we just don’t have enough execution capacity.

The Quarterly: ReNew is among the companies at the forefront of Asia’s energy transition. How do you see this transition affecting the world more broadly?

Sumant Sinha: At the current pace, we’re looking at global warming of three to four degrees Celsius this century. To limit warming to one and a half degrees, we’d need to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

I don’t think that’s possible, because emissions from emerging markets like India won’t peak for several decades. For global emissions to peak, other countries have to become net-negative emitters, and at this point, they’re struggling just to lower their emissions.

The Quarterly: What would it take for the world to change course?

Sumant Sinha: We have to develop new technologies to lower emissions and remove carbon from the atmosphere. That’s the only way to get to net zero. We also need to make an all-out effort to decarbonize industries like cement and steel.

Today, the cost is just not there; companies feel free to put carbon into the atmosphere.

A hefty price should immediately be put on carbon. Today, the cost is just not there; companies feel free to put carbon into the atmosphere. We need to impose substantial penalties. Otherwise, why should any given company rapidly decarbonize? If tomorrow you tell them that the price of carbon is X, and that increases the price of their product by something meaningful like 10, 20, or 30 percent, that’s when they’ll really start investing in cutting emissions.

We need technology development, carbon pricing, and concerted global policy changes. We also need the financial markets and civil society to push in the same direction. It’s a colossal undertaking.

The Quarterly: As a founder, how do you think about ReNew’s purpose, and how has that changed over the years?

Sumant Sinha: Our business is inherently purposeful. In the beginning, we were just trying to survive and get beyond the point of being a start-up. As we’ve become more comfortable about our maturity, we’ve begun thinking more like a market leader. We have to make money and create value for our shareholders, and if we want to access more capital we have to provide returns to our capital providers. But beyond all of that, there’s our social purpose, which is very strong.

We’re working to further our purpose and expand our role in civil society by starting more conversations about the need for a clean-energy transition and creating more pressure to make that transition. We’re talking to policy organizations, think tanks, and NGOs [nongovernmental organizations] about how we can speed up the transition.

We build in remote, underdeveloped areas of India because land is cheaper there. That means that we have an outsize ability to contribute. We’re trying to do something positive in each community, whether setting up a school, digging a well, or supporting women’s entrepreneurship. And we’re getting our people involved so that they embrace the spirit of contributing to society. We want them to bring that selflessness to our business.