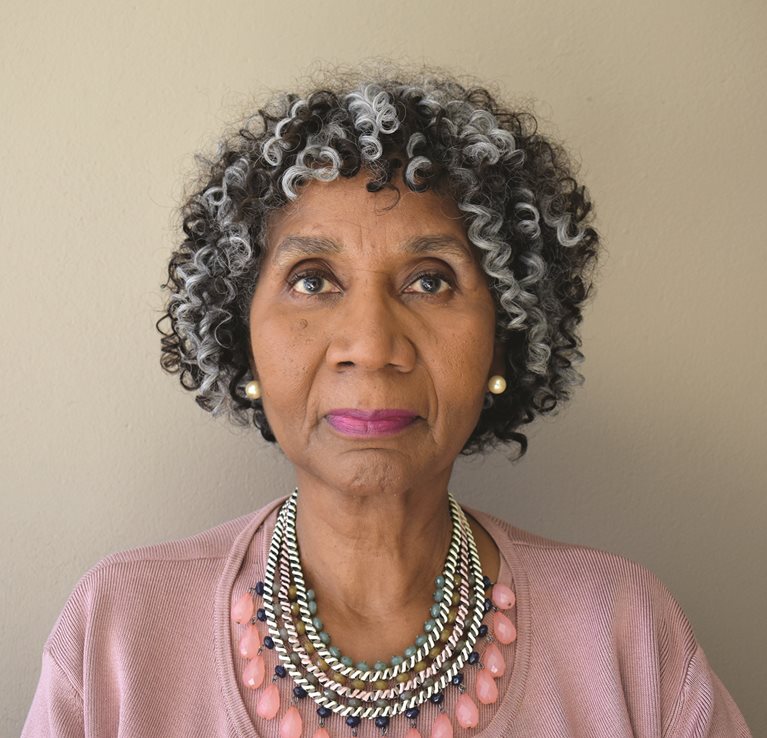

In this edition of Author Talks, McKinsey Global Publishing’s Raju Narisetti chats with Ella Bell Smith, a professor of management at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. In her recently re-released book, Our Separate Ways, With a New Preface and Epilogue: Black and White Women and the Struggle for Professional Identity (Harvard Business Review Press, August 2021), Smith and coauthor Stella M. Nkomo look at the surprising differences between Black and White women’s trials and triumphs on their way to the top by dissecting the experiences of 120 Black and White female managers. An edited version of their conversation follows.

On revisiting the intersection of race and gender at work, 20 years later

This is a bittersweet re-release. If it was under any different kind of circumstances, I would be totally ecstatic. But it’s bittersweet. Stella Nkomo, my coauthor, and I are honored to have this book re-released by Harvard.

Unfortunately, when you look at the statistics in terms of the advancement of African American women, we have seen very little progress. Not in terms of their education level, but in terms of them being able to advance in corporate America. They’re still not where they need to be. We just learned that in Fortune 500 companies, there are now 39 White women and two African American women [CEOs].

That’s not parity with men at all, for neither of the groups. But why can’t we get past just one African American woman? Or two African American women? Can’t there be ten? Something is not clicking. What we’re doing currently in terms of advancing people is not working for African American women and, quite frankly, for all women.

Something is not clicking. What we’re doing currently in terms of advancing people is not working for African American women and, quite frankly, for all women.

How far we’ve come—and how far we have to go

Has anything made an enduring difference in 20 years?

To be brutally honest, no. Have things improved to some degree? Yes. But in very small increments. We take two steps forward, we take five steps backward. Here’s what we know for sure: last summer was a hot year for race and race relations in all the wrong ways in our country.

Systemic racism is very much alive and well. And guess what’s back? The ugly head of White supremacy has made itself clearly visible. It never really went away, but it’s clearly evident in our politics and in our day-to-day lives now.

We’ve spent a lot of time doing kumbaya types of things—building relationships, focusing on racial awareness. We haven’t spent the same quality of time addressing systemic racism: where women get stuck, how they get stuck, the lack of sponsors, wage equity.

Companies are not developing [Black women] or spending money [on Black women] or making sure that Black women have the skills, the polishing, to be able to take senior positions, to be able to get the positions that are going to bring in revenue.

Many women are getting promoted now, and that’s exciting—Black women, Brown women—a lot of them are going into D&I [diversity and inclusion] positions. That’s not going to bring in revenue. That job is not going to make you a top-game player. It’s not going to put you in competition with the White men for those high-profile, revenue-earning [jobs]. So we need a different approach to really understand how to advance all women, but particularly Black and Brown women. And I would put Asian women there, too. I think Asian women get trapped in technology jobs.

Why should we be more hopeful this time around?

The thing that I am hopeful about is the environmental context, what’s happening in our society. What I saw last year with the George Floyd tragedy and Breonna Taylor and all the others, when I saw the protests, I saw young Whites in those protests. I never saw that before, to that degree. Yes, in the ’60s we had the Freedom Riders and all that. But to see young, White, Black, Asian, Brown faces in these protests, of all ages, it was heart-striking to me. I think there’s a greater awareness in the broader society right now, which makes me hopeful.

I am concerned about how corporations respond. There is the external response, and companies are really good with the external response. Black Lives Matter has money. The historically Black colleges have money.

Corporations were very generous, and that’s fantastic. But they also have to [invest] the same type of energy internally. What’s going on inside their companies in terms of the advancement, the succession, the retaining, the pay equity, of their Brown and Black people, particularly their women?

I’m not sure equal time was given, and I’m not sure how long equal time was given. This is not something that you can check the box on. If anything, we know that this is continual work that needs to be done.

It’s time for a new approach

What can companies do differently this time around?

We need to start looking at the boards of directorships. Who has expertise in D&I? Particularly inclusion. Diversity’s just your numbers. You know, what does your demographic profile look like? You really have to work on inclusion, building trust, building equity systems, understanding the systemic blocks in the system—and on belonging, so that I feel like I’m really belonging to your company.

There needs to be people on the board who understand and recognize and have these kinds of frameworks in their heads, quite frankly, this expertise, this talent. There are things that we still need to do. Activities, actions, still need to be taken.

As long as companies do the “kumbaya, we feel good” and check the box and then say, “OK, we don’t have to do this anymore,” I don’t think we’re going to get there or see difference in the long term. I’m looking for a sustainable difference. I’m looking for radical change so that we don’t have to keep having this conversation 20, 30 years later. I don’t want this conversation to be had 20 years from now.

We need to get comfortable with difficult language like “systemic racism,” “systemic sexism,” and the intersection of those two. We need to understand the impact it has on all employees, and particularly employees of color. We need to dig deeper. We need to monitor. The person doing the belonging work needs to report directly to the CEO. We need to be sure that we’re constantly tracking and monitoring. We need to be sure that we are developing our people—all of our people—including to the high-profile programs. Given the demographics and how the demographics are changing, you can no longer say or use as an excuse, “We haven’t gotten to that group yet.” That just doesn’t work anymore. That is not the right answer.

We need to get comfortable with difficult language like ‘systemic racism,’ ‘systemic sexism,’ and the intersection of those two. We need to understand the impact it has on all employees, and particularly employees of color. We need to dig deeper. We need to monitor.

How do you repair the still-fractured relationship between Black and White women in the workplace?

I am happy to say I have seen progress on that, and to really begin to build sisterhood and coconspirators. Why do we think that White women understand race any more than White men? Race is a cultural phenomenon. We learn about the traditions, how we communicate, how we think about our belief systems, in our families, in our communities. And White women grow up, for the most part, in White, monocultural communities, just like White men. They haven’t had contact with Black girls. They haven’t had interactions growing up. They’re susceptible to the same stereotypes, the same myths, the same lack of empathy, lack of interaction, as White males are. And sometimes, it’s even more extreme because there’s the issue of competition between women.

People get angry when I say this, but sometimes White women don’t support each other very well. So you start asking White women to connect across a racial line with a woman they have had very little interaction with, a woman they don’t really know very much about.

The other reality is that White women are more familiar to White men. They’re their mothers, they’re their wives, sisters, girlfriends, daughters. Think about the interactions that White women and White men have had with Brown and Black women and those kinds of relationships. How did they learn about race?

It makes a big difference for being able to come together and to be able to support each other. The other thing that’s really interesting in terms of value systems is that we have different orientations. Black women are taught early on to support others in their community.

Reach back. Lift others up. It’s not a caretaking; it’s a support. It’s a belief. It’s an anchoring. It’s in our DNA. White women don’t necessarily have that. They come out of a highly individualistic culture. Pull yourself up by your bootstraps.

So when you start talking about value orientations, there’s not a whole lot there to weave the two groups together. Enter the term “coconspirator.” “Allies” is nice, but an ally can come and go. An ally can say, “This is not something I’m really interested in. This is not going to help me.” But coconspirator? Basically, you’re going to support me no matter what. We’re in this. We have equal skin in the game. We will face the win on this together. But we will also face the consequences. That’s an important kind of relationship to build. You’re going to use your voices. You’re going to strategize. It’s action. Allies doesn’t necessarily imply action all the time.

Coconspirators means action. And we need action on these issues. Women will not advance until we bring our voices together. As long as we’re divided, it’s easy to conquer us. When we become united, that’s a whole different matter [people] have to deal with.

Women will not advance until we bring our voices together. As long as we’re divided, it’s easy to conquer us. When we become united, that’s a whole different matter [people] have to deal with.

Coconspirators come together. How did we create these relationships? Honest dialogue. Sometimes very uncomfortable. Being able to realize it’s not about you all the time. Being inquisitive. Learning about each other. And being able to really connect and realize that what impacts one is going to impact the other.

Reflecting on progress

Aren’t you personally better off today as a professional Black woman than you were 20 years ago?

Oh my God. Let me give you some background. I was raised in the South Bronx. I’m adopted. My mother had a sixth-grade education. My dad had an eighth-grade education.

I had some really poor education. My foundation was horrible. My foundation was never developed in the New York City school system, where I started in the South Bronx. They just did not develop us or teach us.

I am amazed today at the schools that I’ve taught at. This is my 21st year at Tuck. I am truly blessed. I’ve had an opportunity, particularly at Dartmouth, to grow and to expand and to make a difference the way I wanted to with the support of the deanery.

I have nothing to complain about. I might be the exception to the rule. I have seen advancement, but I’ve also seen doors closed in my face. I’ve also heard, “Well, we’re not ready to have a Black woman be a keynote” or “We’re not sure you can work with White men and make a difference” or “We’re not sure that you can really lead that charge” or “We’re not sure that you’re worthy of promotion and of tenure” and all those other trappings in higher education that we don’t ever talk about, which are just as hard and brutal, if not more so, as in the corporate world.

So am I better off? As I’ve aged, I’ve also learned what battles to pick. Some battles are not worth fighting. And I also know that nobody does this alone.

I’ve been very lucky, blessed, to have amazing sponsors—both academic and corporate. I’ve been very fortunate to have a network of women of all races, to really support me and lift me up. I have matured to the point where I now know how to develop and build those relationships. I think that takes time.

That’s why I’m so driven to make sure that for younger Black women and Brown women, and just women in general, there’s a way to navigate this. But we’re putting all the burden on the women, which is not right. We expect the women to make all the changes. No. It’s time for corporations and society to recognize, that’s no longer going to work. Corporations have to start doing this much better.

We have also seen the grit, influence, and grace of Kamala Harris, Stacey Abrams, Michelle Obama.

Grit, influence, and grace. We always have one or two. We get one African American woman, one Brown woman, one Asian woman. There’s one. We have to get past our “only one.” I love our vice president, [Kamala] Harris. Stacey Abrams, I bow to her feet any day. But that’s one. They’re not in the corporate sector, they’re in the political sector. It’s a different kind of way of surviving in the corporate [sector].

It gives me hope. It makes me proud for my granddaughter. “Yes, there are role models. You can be anything you want to be. She did it; you can do it.” But when it comes to developing more women, we can’t stop at one. One story, one shero, is not going to work. And what happens is we get the ones.

There are so many fabulous women scholars of all races, particularly Black and Brown, coming up behind me. We’ve got to recognize that there’s more than one. And we’ve got to celebrate all. Not just the ones. We get stuck on the ones. I want multiples. Multiple celebrations.

Watch the full interview