Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a common concern expressed by CEOs of American companies was that the United States suffers from a shortage of qualified talent, which makes it difficult for their companies to fill their most in-demand jobs in management, technology, and healthcare. Yet there is a population of people who are rarely considered for these in-demand jobs: the more than 70 million American workers who have a high school diploma but have not completed a bachelor’s degree.

While these workers make up the vast majority of the US labor force, they often face a frustrating challenge when searching for new jobs: most middle-wage and high-wage jobs list a bachelor’s degree as a requirement. Many companies use recruiting software that automatically screens resumes for the degree. As a result, many skilled workers never even apply for jobs they can perform, and, when they do, their resumes may never be reviewed by a person.

Making matters worse is the fact that workers without a bachelor’s degree are disproportionately affected by automation and COVID-19-related job losses. According to a 2019 report by the McKinsey Global Institute, during the coming decade, workers without a college degree are four times more likely than those with one to lose their jobs due to automation. Moreover, as measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 have led to economic shutdowns, workers without college degrees have experienced the greatest losses in employment and income.

These many workers have skills that are under-recognized and underused. With training and support, they could build skills that position them for attractive, higher-wage, more resilient, in-demand jobs that employers find hard to fill. To support them effectively, it is crucial to start by examining the data: What advances have a large number of people achieved, building on their skills to improve their economic circumstances?

In 2019, McKinsey launched a research effort to help employers move beyond the degree screen and increase the pool of talent they consider for their most in-demand jobs, while helping to create opportunities for people to achieve economic mobility. With input from the McKinsey Global Institute, our analytics team sought to map the actual pathways people have taken in moving from low-wage, declining jobs to middle-wage and higher-wage jobs of the future. To make sure this research reflected the real-world needs of workers and employers from the outset, we were significantly aided by Opportunity@Work, a nonprofit organization that seeks to increase career opportunities for millions of US adults who are skilled through alternative routes. They provided input on the challenges faced by these workers, helped validate pathways with workers and employers, and suggested research priorities to inform a more inclusive and equitable labor market.

In turn, we are putting our research insights to use. As a start, we have been working with the Markle Foundation, as their partner in the Rework America Alliance, to translate the analytics into usable market signals that give workers more targeted guidance on reskilling opportunities—leading to better wages and better quality jobs—and more targeted insights on which training options best fit their reskilling needs.

The analytical approach

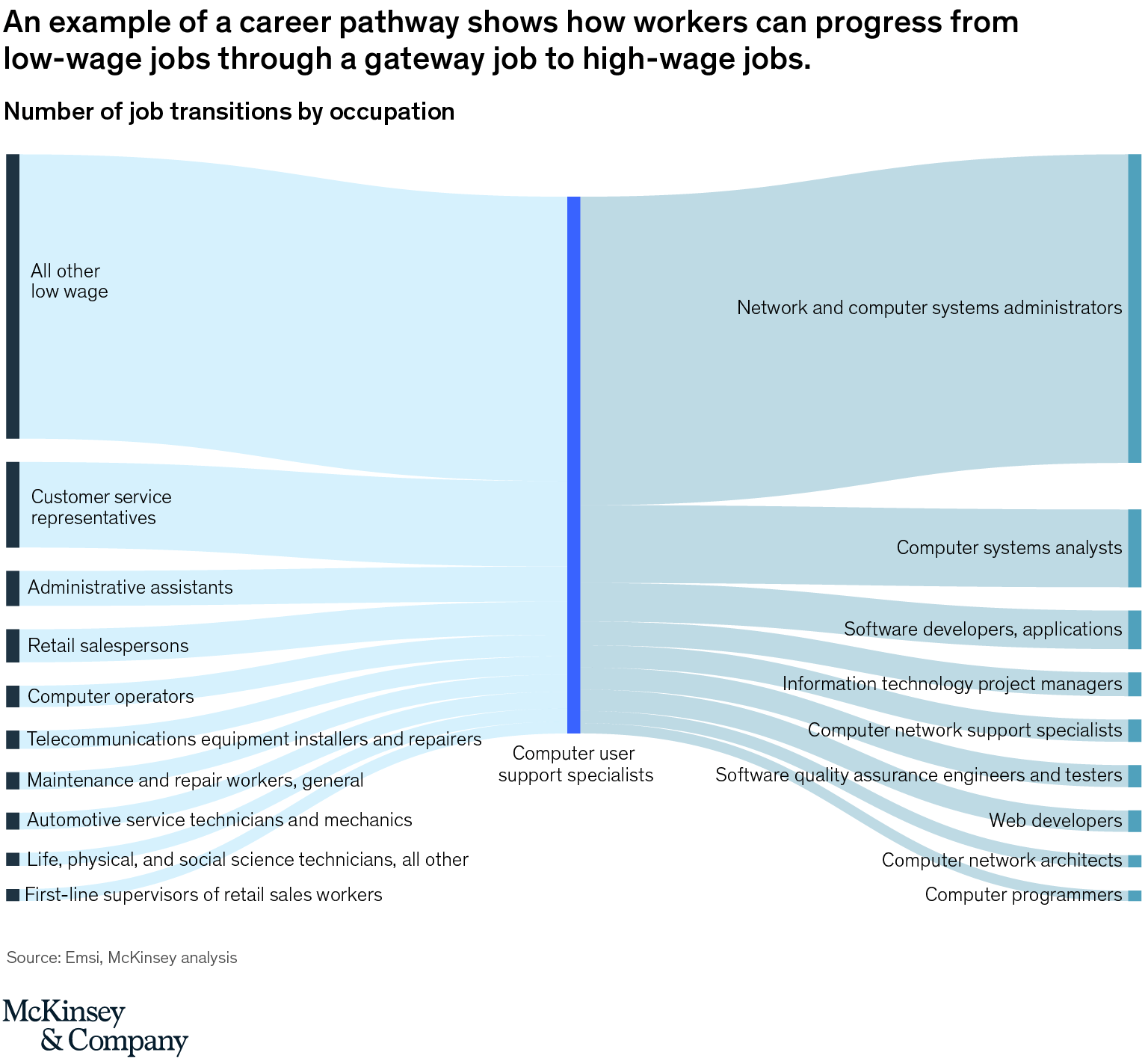

We began with a data set of more than 60 million anonymized talent profiles and job histories and more than 150 million job postings collected from Emsi, Burning Glass, and Eightfold.ai (note: McKinsey has supported Eightfold and FMI to build an AI platform to help match people to jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic). Within this data set, we looked at people without bachelor’s degrees and at least three jobs in their job history in order to understand of how people have made the transition between jobs and built skills and experiences. We also mapped their transitions from low-wage “origin” jobs to “gateway” jobs, which unlock higher-wage work, and finally to “destination jobs,” those likely to continue growing in the future (Exhibit 1). As a practical starting point, we focused on three areas: technology, healthcare, and business management (see sidebar “About the methodology”).

Key findings

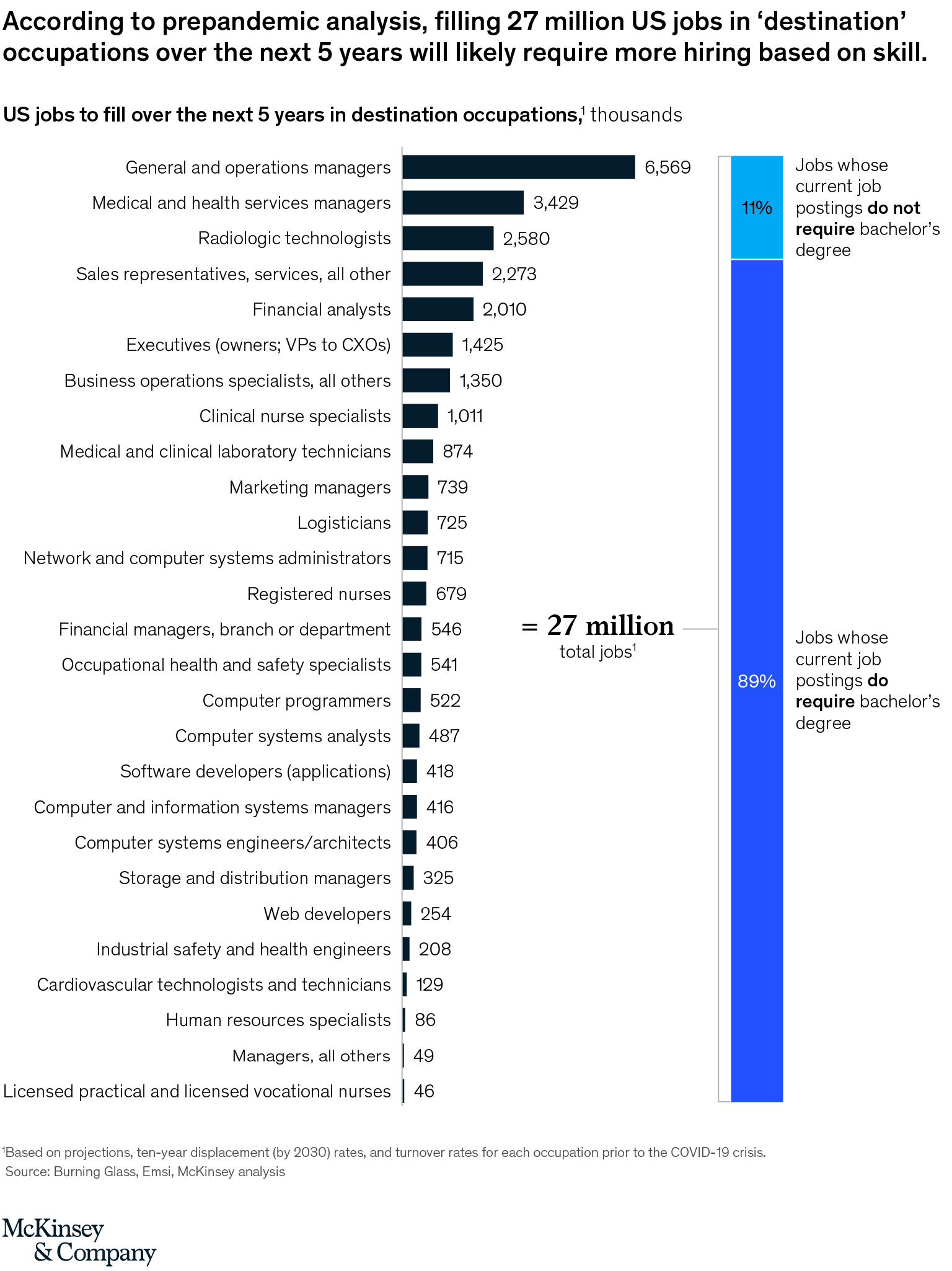

The number of the most in-demand destination jobs in technology, healthcare, and business management is growing, and filling them will require hiring managers to take a skills-centered view of candidates. We focused on a subset of jobs with growing demand in the fields of technology, healthcare, and business management. These destination jobs have a median annual salary of $65,000, are resilient to the risks of automation and COVID-19, and have proved to be accessible to skilled workers without a bachelor’s degree. Analysis conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that in the next five years employers will need to fill about 27 million such jobs—a figure that doesn’t include similar or adjacent occupations that could arise (Exhibit 2). While destination jobs can and should be viable options for workers without a bachelor’s degree, 89 percent of current job postings list a bachelor’s degree as a requirement.

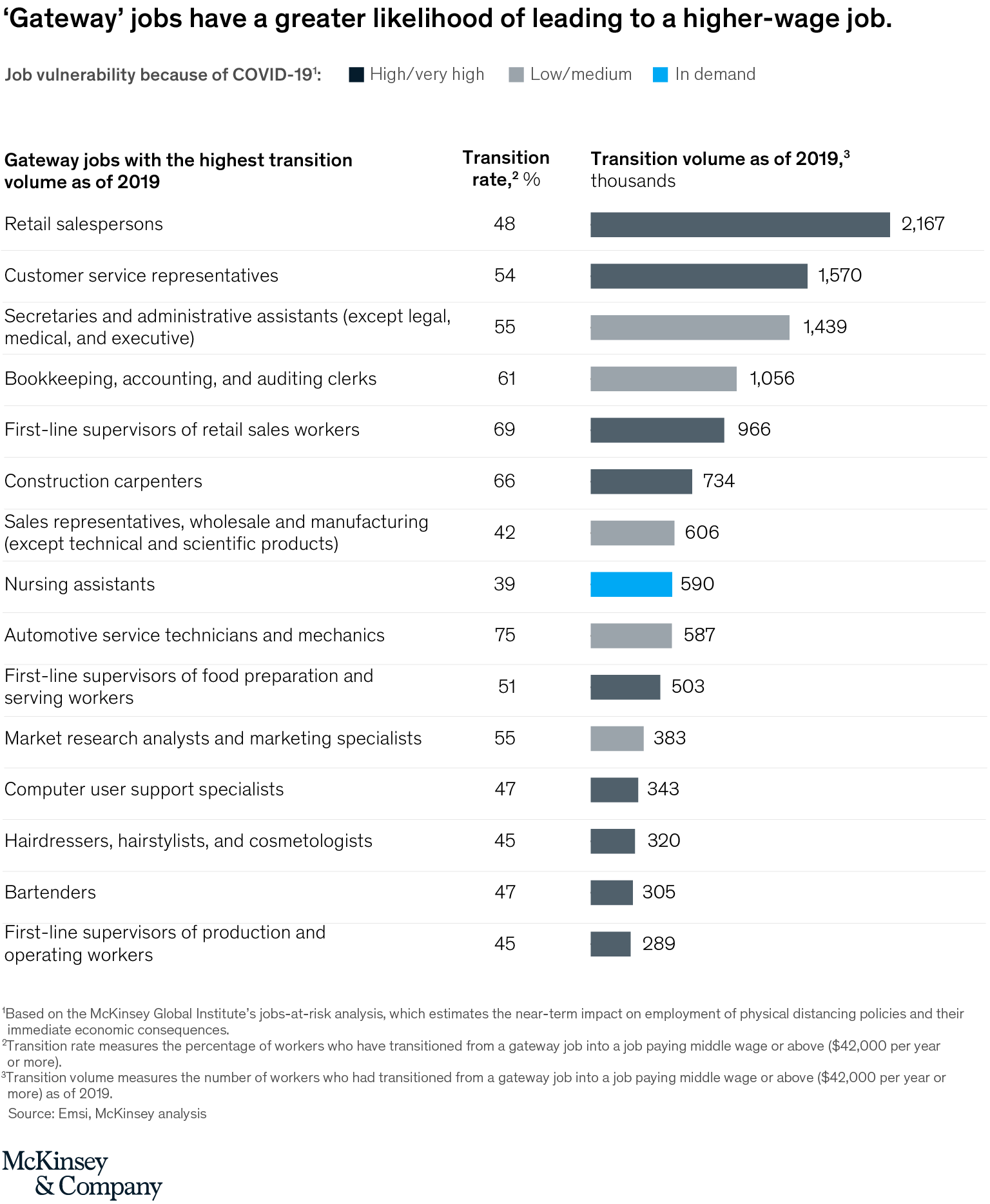

Gateway jobs are the stepping-stone positions that have a greater likelihood of leading to middle-wage or higher-wage jobs. We identified 38 high-volume occupations that have the greatest likelihood of leading to a higher-wage, in-demand destination job (top 15 are shown in Exhibit 3). In 2019, approximately 32 million workers were employed in these occupations, though shutdowns related to COVID-19 have affected many of them.

Because of COVID-19 shutdowns, some gateway jobs have high or very high vulnerability to inactivity that could lead to reduced income, furloughs, or even layoffs. Expanding opportunities for people in these gateway jobs to make the transition to higher-wage destination jobs could create meaningful wage growth for tens of millions of US workers.

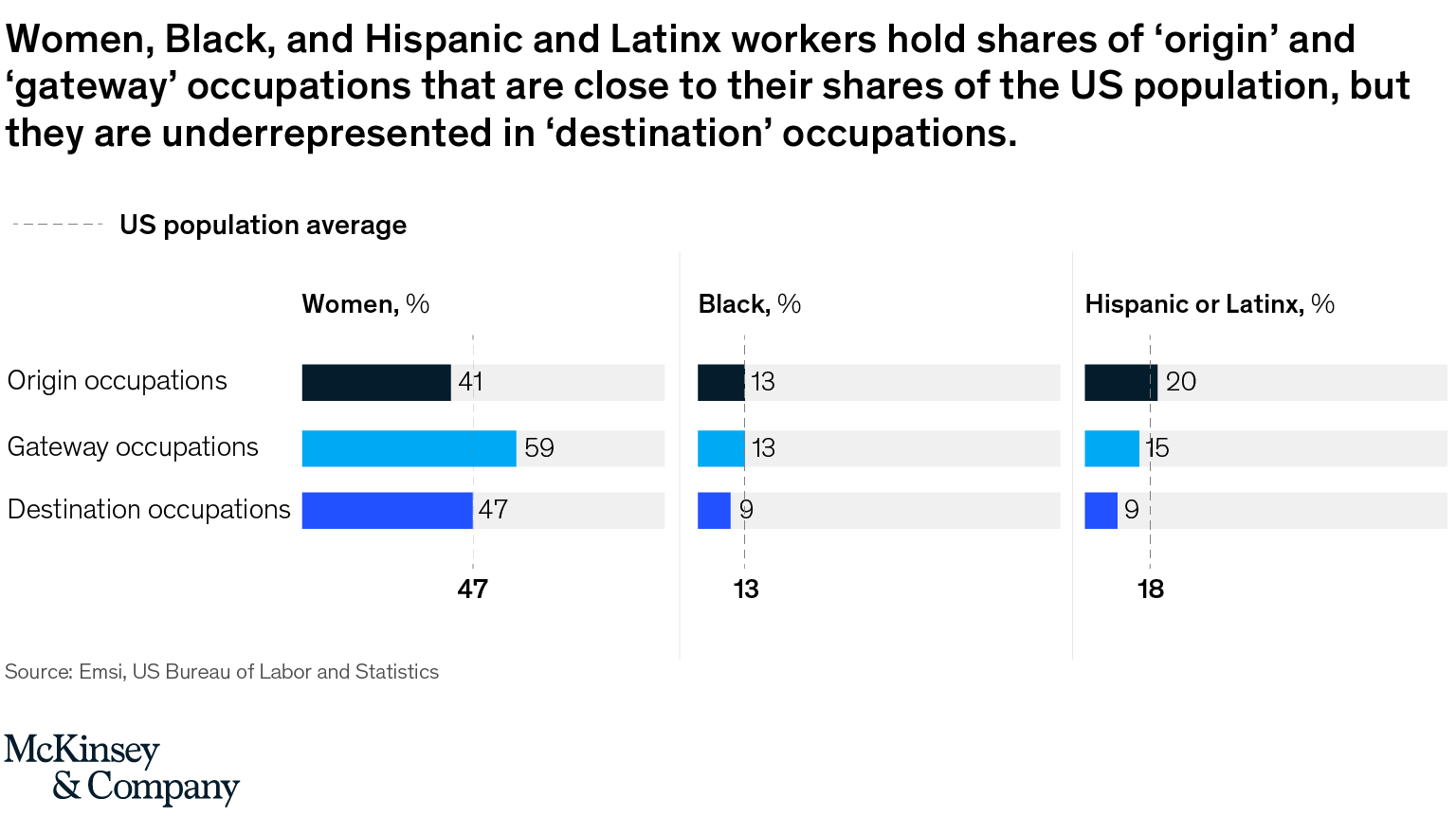

Employers can improve the representation of women, Black, and Hispanic or Latinx workers in destination occupations by intentionally recruiting from gateway jobs, which are held by a more diverse population. The in-demand destination jobs we identified have a lower-than-average representation of Black and Hispanic or Latinx workers. Holders of gateway jobs, however, are more diverse and more closely mirror the demographics of the country. Women make up 59 percent of workers in gateway jobs, more than 12 percent above the national average. Intentionally hiring workers who have built skills while in gateway jobs can help employers improve diversity in their most in-demand, higher wage jobs (Exhibit 4).

Next steps

In the coming weeks, we will share further insights from this research, including the full set of gateway jobs and more details on pathways that lead to in-demand destination jobs. We also know that this research is just a starting point. It draws on historical experience that may only partially inform the future, given the disruptions caused by the pandemic; we plan to expand on the analysis to account for those effects.

Our goal is to do more than publish research. We also intend to make the insights useful to practitioners involved in advancing wage mobility, skills-based access to opportunities, and a more inclusive economy. The many relevant applications for these findings include helping workers dislocated by COVID-19 to identify reskilling opportunities that serve them best, helping employers to tap a large pool of overlooked talent, and helping educators to create training options that will most improve people’s wage and job prospects.

We welcome input on how to make this research, and the analytical advances to come, as useful and relevant to the needs of workers as possible.

For more information, please contact Nikhil Patel, a partner in McKinsey’s Houston office, or Carolyn Pierce, head of product management in the Southern California office.