Wholesale banking in India is set for a period of sharp growth. Revenues from wholesale banking activities are likely to more than double over the next five years as infrastructure investment, expansion by Indian companies overseas, and further “Indianization” of multinational businesses, among other trends, drive new business. Foreign players and the country’s domestic banks, however, will find themselves in a tough commercial environment and must overcome a range of challenges if they are to maintain, or assume, a leading position in the market.

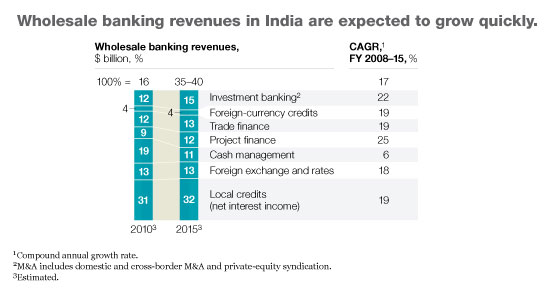

Prospects for India’s wholesale banking market are intriguing. Wholesale banking revenues, which in India account for close to 30 percent of total banking revenues, are expected to more than double, from roughly $16 billion in fiscal 2010 to between $35 billion and $40 billion by 2015 (Exhibit 1). McKinsey’s analysis shows that returns on equity are typically in the range of 15 percent to 30 percent.

Corporate banking, including both lending and fee businesses, accounts for the lion’s share of the wholesale market—about 85 percent. Revenues from this source are projected to grow at about 19 percent annually, reaching $30 billion by fiscal 2015.

Investment banking and markets, checked by the slowdown in the global economy, should bounce back. We estimate revenues will rise from $1.8 billion in financial year 2010 to reach $6 billion by financial year 2015, an annual increase of 27 percent. Equities (primary origination and secondary trading) are expected to account for close to 70 percent of this total, M&A for 20 percent to 25 percent, and debt capital markets and private-equity syndication for between 5 percent and 10 percent. The recent rise in equity markets and the subsequent pickup in M&A activity are already being felt.

This article will examine the trends underlying the expected levels of growth, then address the key issues and priorities from the perspective of foreign institutions and their domestic counterparts.

What’s driving growth

Several trends will shape the evolution of India’s wholesale banking markets and create new opportunities for foreign and domestic players alike:

An expected surge of infrastructure investment, creating demand for additional banking products and services

The continuing globalization of Indian companies, bringing with it the need for acquisition expertise, trade-finance and treasury services, and cash-management skills

Growing interest in the “India story,” inspiring a host of inbound M&A deals and increased fund allocation by global managers

Increasing sophistication of products and solutions, driving higher margins

A continuing focus on midmarket companies with new banking requirements

Regulatory change in bond and equity markets

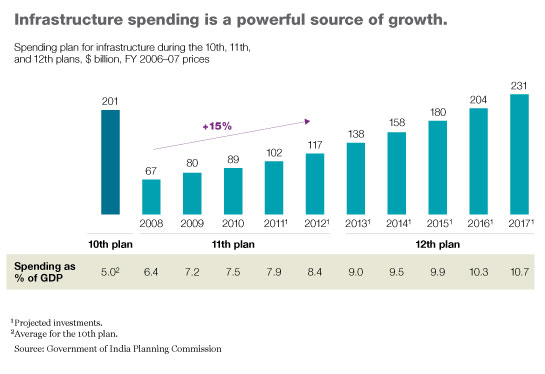

Infrastructure investment

Investments in infrastructure totaling $240 billion between 2007 and 2010 have already been made under India’s 11th Five-Year Plan, and it is projected that investments under the plan will reach $500 billion, or roughly 8 percent of GDP, by the end of 2011. Demand for core infrastructure will nevertheless likely outstrip supply in the future. To sustain India’s economic growth, the Planning Commission therefore envisages that $1 trillion (about 10 percent of GDP) will be spent on infrastructure during the 12th plan from 2012 to 2017 (Exhibit 2).

According to the Planning Commission, half of the investment during the 12th plan, or some $500 billion, is likely to come from the private sector, implying a more than threefold increase in private-sector investment over the 11th plan. Another $250 billion is likely to be raised by the public sector through external financing. Meeting these investment needs could create annual wholesale banking revenues of $6 billion to $7 billion across lending, debt syndication, capital raising, and secondary markets. But banks must be willing to innovate, potentially becoming active developers in addition to operating through third parties, and they must also embrace more sophisticated products, such as project financing, through a mix of syndicated lending in foreign currencies, nontraditional structured-trade-finance instruments, and securitization of cash flows.

Managing asset-liability mismatches will be a key challenge that will require institutions to broaden the sources of funds for projects beyond bank financing. Services such as bond placements and credit enhancement should provide additional sources of revenue as the corporate bond market deepens and the regulatory framework for introducing longer-term sources of funds (for example, insurance and pension funds) is put in place.

Globalization of Indian corporates

Close to 60 percent of Indian companies expect to increase their share of overseas business over the next five years, according to McKinsey’s globalization survey.1 This development, which will take the form of greater exports, increased international operations, and expanded sourcing, will create three types of opportunities for wholesale banking players:

Acquisitions. Outbound acquisitions by Indian companies in the first seven months of 2010 amounted to $22 billion, significantly higher than the $8 billion recorded in 2009; it also exceeded the total in 2007, before the crisis. This acquisition spree looks set to continue, as global targets become cheaper and competition from international financial sponsors, such as private-equity and leveraged-buyout firms, diminishes.

Trade finance and treasury. As Indian companies expand trade with other countries, the need for services such as letters of credit, export insurance, structured foreign-exchange solutions, and receivables financing increases.

Cash management. Companies with global operations have to manage cash flows at a global level and therefore require more complex and sophisticated solutions.

‘Indianization’ of the capital markets

Inbound M&A deals amounted to a healthy $80 billion between 2006 and 2010, a trend we expect to continue as multinational corporations increasingly respond to the “India story” and take advantage of easier foreign-direct-investment regulations. The new wave will provide fresh deal-structuring, treasury, and trade-finance opportunities. Foreign banks are aggressively leveraging global relationships to support international clients as they craft their Indian entry plans, but domestic players can use their domestic balance sheets to win a share of the action.

Simultaneously, global institutional investors are increasing their allocations to emerging markets, including India. Our conversations with some of these large players suggest that the allocation to emerging markets could rise to 18 percent to 25 percent from 10 percent to 12 percent. As of January 2010, long-only funds among foreign institutional investors (FIIs) had invested around $81 billion in India, or about 25 percent of their major emerging-market flows. More FIIs are registering in India,2 while several top global private-equity and venture-capital firms have established offices in the country. For several of these players, India is among the top three or four global destinations outside their home market where they have an on-the-ground presence.

The enhanced interest in India is likely to stimulate primary and secondary equities markets in the coming years.

Increased product sophistication

Trade finance accounts for about 12 percent of corporate banking revenues and will likely continue at these levels. But while demand for traditional, low-return products (for example, letters of credit, bank guarantees) will grow, demand for more sophisticated, bundled foreign-exchange and derivative structures will grow even faster. Leading players, we believe, will continue to pursue areas such as factoring, supply chain finance, and structured trade finance. Supply chain finance and factoring are already significant markets in their own right, with total revenues projected to exceed $1.4 billion by 2012. Structured trade finance, particularly export-backed commodity financing, is growing at 20 percent to 25 percent per annum.

Given that the share of Indian imports on open accounts is just 15 percent to 20 percent, in comparison with an average of 50 percent to 60 percent in the rest of Asia, companies will likely look to banks to provide an integrated working-capital solution. Banks, for their part, are moving to create integrated sales forces as well as technology platforms that straddle the two products.

Midcorporate enthusiasm

With intense competition and therefore lower margins from servicing large corporate customers in the future, the midmarket will remain a critical area of wholesale activity. The typical corporate banking return on equity for serving midsize corporations in India, for example, is about one-and-a-half times that of the large-company segment.

Midmarket companies already represent a third of the overall wholesale banking market. But as their ambitions grow, these businesses will demand more sophisticated instruments, such as capital market products and derivatives, not just traditional products, such as lending and trade finance. Midcorporates will also feature more in private-equity deals in India, which currently average around $38 million.3 These small deals constituted about 25 percent of the $6.5 billion of private-equity syndication volumes in 2009. Commercial banks with a significant midcorporate franchise have the opportunity to create a private-equity syndication franchise.

Regulatory change

In most developed markets, corporate bonds represent a significant part of overall wholesale banking revenues. In India, however, the corporate bond and securitization markets are nascent, with total revenues of approximately $30 million in 2010,4 compared with total equity capital market (ECM) revenues of about $390 million. Several regulatory issues have affected the growth of the market, notably the substantial disclosure requirements, limits on pension funds and insurance companies, restrictions on upfront profit booking of gains from securitization, and the introduction of a rupee-for-rupee capital requirement for both first- and second-loss credit enhancements.

Bond issues in the future will increase as liquidity tightens and banks face capital pressure following the implementation of Basel II; however, for the market to really take off, more regulatory easing will be required. For example, companies can create a credit-enhancement product for bonds, reduce “haircuts” on corporate bond repos to create a viable repo market, simplify bond-listing requirements, and reduce stamp duty on corporate bonds from 0.375 percent to 0.250 percent per annum across all states.

As for equities, the Indian bourses must increase domestic retail and foreign investor participation. A raft of regulations focused on corporate oversight, enhanced investor protection, and convenient participation is expected. For example, the Securities and Exchange Board of India recently issued several important guidelines on book building, disclosure norms, and Indian depositary receipts rights.

Imperatives for success

While corporate lending and trade finance account for about 80 percent of the revenues of Indian banks, particularly public-sector ones, foreign banks derive 60 percent to 70 percent of their business from treasury, capital markets, and investment banking. Foreign players, for example, hold a 60 percent to 75 percent share of ECMs, M&As, and derivatives. Public-sector banks, on the other hand, dominate “balance-sheet-heavy” segments such as corporate lending and plain-vanilla trade finance (letters of credit, bank guarantees).

These starting positions are by no means fixed, and the picture is changing rapidly, especially post-crisis, as Indian banks focus more of their energies on fee income to drive wholesale profitability. That said, foreign and domestic banks will need to set different priorities to deal with the challenges ahead.

An agenda for foreign banks

We see three key priorities for foreign banks: reaching out to the midmarket, overcoming their lack of domestic balance-sheet muscle, and leveraging synergies in corporate and investment banking.

Improve distribution to reach midcorporates and small and midsize enterprises (SMEs). About 45 percent of foreign banks’ branches are concentrated in metro areas and Tier 1 cities because of restrictions on the number of bank branches they can open. Foreign banks thus struggle to serve midcorporates and SMEs outside these cities. As a result, foreign banks have focused on large corporates. However, faced with growing competition and margin erosion in their large-corporate business, foreign banks must develop cost-effective ways to serve profitable midcorporate and SME segments. For example, they could offer products such as supply chain finance, which will enable them to target SMEs and midcorporates that are suppliers or distributors for their large corporates.

Overcome rupee balance-sheet disadvantage. Foreign banks in India are limited by the size of their rupee balance sheets. As Indian banks start flexing their muscle and demanding a higher share of non-fund-based business (exploiting their lending relationships), foreign banks must find ways to overcome this disadvantage, perhaps by offering clients unique structuring, lines of credit, and off-shore products.

Leverage synergies across corporate and investment banking. Foreign players have created high-cost, siloed units in corporate and investment banking. Only by moving from product-centric to client-centric models will they be able to capture a higher share of business in areas such as infrastructure and trade finance. While domestic players leverage their corporate banking capabilities and relationships to make inroads in investment banking, foreign players can use their superior investment-banking capabilities and relationships to make greater headway in corporate banking.

Priorities for local institutions

Domestic banks have five priorities:

Enhance capabilities to play in the non-fund-based business. Thanks to their widespread branch networks and retail customer franchises, Indian banks (particularly public-sector banks) have been able to deploy a large deposit base in their lending. However, they have not been able to build on their strong lending relationships to expand into non-fund-based businesses (such as transaction banking, foreign exchange, treasury, and capital markets). That means developing new capabilities, including customer-coverage and account-planning processes, product design and structuring, and risk management, to provide a full suite of competitive products and to deepen client relationships.

Build offshore business models. Wholesale products will become more global as Indian companies expand their international operations and new regulations facilitate international capital raising. Foreign banks are in a strong position to dominate these product markets because they have strong international balance sheets and better credit ratings. But given growing demand from Indian corporates for access to non-rupee funds both in India (in the form of external commercial borrowings) and globally, Indian banks can respond by establishing a presence in key global financial centers (for example, Singapore and London) and by building appropriate funding and distribution capabilities to serve customer needs.

Attract and retain top talent. Foreign banks have used higher remuneration and perceived brand value to attract and retain quality staff in areas such as treasury, investment banking, and relationship management. They have the talent base to structure complex cross-border M&A transactions or create exotic derivatives for their clients. Their Indian counterparts will have to acquire these capabilities if they are to compete. A few private-sector Indian banks have done so, but most struggle to develop an appropriate value proposition to attract and retain talent.

Put in place a robust technology platform. Technology will be a key differentiator, particularly in scale-intensive wholesale businesses like transaction banking (trade finance and cash management) and foreign exchange and equities. Most large corporations, for instance, are now looking for secure online trade-finance and cash-management platforms that are integrated with their core enterprise-resource-planning systems. While several Indian private-sector banks have cutting-edge technology and can compete with foreign banks, others will need to make significant investments to catch up with their peers.

Enforce account-management discipline. As Indian players expand their wholesale activities, they need to adopt best practices in account management, including key account planning. They must also use a management information system that highlights individual client profitability and maps clients with relationship managers and product specialists. Our experience is that this effort requires significant organizational commitment and a willingness to break traditional boundaries.

After dipping last year, the Indian wholesale banking market is poised for new growth on the back of the rosy prospects for India’s companies. Foreign and Indian players are at different starting points, given their different capabilities and market shares. But the opportunity is huge for those that make the right choices and execute their strategy well.