Kaiser Permanente (KP), the largest nonprofit health plan in the United States, is renowned for the tight integration of its clinical services. KP closely coordinates primary, secondary, and hospital care; places a strong emphasis on prevention; and extensively uses care pathways and electronic medical records. By doing so, it provides its 8.7 million members and patients with high-quality, cost-effective care.

That KP can achieve such tight integration and strong results is especially remarkable in that it is not one organization but several cooperating entities (see sidebar, “Kaiser Permanente at a glance”). All these entities share a common vision: to deliver coordinated, comprehensive health care that keeps patients as healthy as possible.

To find out what other health systems can learn from KP’s experience, the Quarterly recently spoke with Harold “Hal” Wolf III, senior vice president and chief operating officer of the Permanente Federation, the national umbrella organization for the Permanente Medical Groups (the physician component of KP). Ben Richardson, a principal in McKinsey’s London office, conducted the conversation.

The Quarterly: What are the benefits of integrated care?

Hal Wolf: KP carefully coordinates the work done by primary care physicians, specialists, hospitals, pharmacies, laboratories, and others. This approach offers several advantages. It improves care quality, makes care delivery more convenient for members, and increases communication among all the people providing care. It also enables us to find efficiencies that reduce costs, improve or maintain quality, and allow for innovation.

We believe strongly in evidence-based medicine, and we are always looking for innovative ways of delivering care. When we find an innovation that is working well, we want to propagate it as best practice throughout our organization.

The Quarterly: How do you provide integrated care?

Hal Wolf: We operate in nine states and the District of Columbia, and our operations are slightly different in each area. In all cases, however, we integrate care as closely as possible. In California, for example, we provide members with an end-to-end experience; we own and operate a large number of clinics, hospitals, laboratories, and pharmacies. At all our clinics, patients can receive primary and secondary care; at most, they can also undergo laboratory and imaging tests and get prescriptions filled. At some clinics, they can even undergo same-day outpatient surgery. This way, we take care of most of our patients’ health care needs in a single facility.

Our primary and secondary care services are closely intertwined in California. Our primary care services include everything from basic health checkups to disease-management programs. Those programs include appropriate specialist consultations when needed, but primary care physicians remain in charge of patients’ overall care. Even if patients need to be hospitalized, care delivery is seamless because all physicians and other health professionals have access to KP HealthConnect, our electronic medical record database.

In Colorado, our services are similar, but we don’t own our own hospitals. Nevertheless, we have extremely close relationships with our partner hospitals. For example, the physicians who take care of our patients at these hospitals are part of the Colorado Permanente Medical Group and have full access to KP HealthConnect. As a result, they are able to view a complete medical history for their patients, and we are able to compile a complete record of what happens to our patients while they are hospitalized. Because KP HealthConnect updates itself in real time, the records are never out of date. If a patient leaves a clinic and drives to a hospital, the physicians at the hospital can see the clinic records as soon as the patient arrives.

The Quarterly: What are the organizational enablers that allow you to deliver integrated care?

Hal Wolf: Integrated care requires everyone involved in the patient’s care to work as a team. Each person—whether delivering primary care, secondary care, pharmacy management, or something else—must ask: what are our goals for this patient? What opportunities do we have to achieve a better outcome? In other words, each team member must focus not only on the particular treatment he or she is providing but also on the entire care pathway. If this type of integrated approach is used with every patient, then KP is meeting its goal, which is to improve the overall health of the community, one person at a time.

The fact that we are a payor as well as a provider helps in this regard. As a payor, we can make certain that the right incentives are in place to help ensure that all team members work together in harmony.

Another key enabler of integrated care is a good IT system. Without one, it is impossible to gather and share information, track outcomes, or systematically identify innovations thatimprove patient care. However, a good IT system is not sufficient on its own to ensure that care is integrated.

The Quarterly: Please tell us more about how KP works with hospitals it does not own.

Hal Wolf: We view our relationship with these hospitals as a partnership, and we work closely with them to ensure that their quality and performance goals match ours. We rely on our partner hospitals to serve our members, and so we have a responsibility to help ensure their success. For example, we’ll investigate whether we can do anything to help our partner hospitals meet their quality standards. Often, we are deeply integrated into the hospitals’ operations because their clinical departments are led by Permanente physicians. Of course, we also track hospital costs—cost per day, cost per procedure, etc. This allows us to negotiate the rates we pay to the hospitals and helps ensure we are being billed appropriately.

The Quarterly: How do you develop your care pathways? And how do you support their use?

Hal Wolf: The care pathways are developed by multidisciplinary teams using evidence-based medicine, and they are one of the fundamental ways in which we integrate care. Roles and accountabilities are clarified in the care pathways. For example, our physicians provide only part of patient care; the remainder is delivered by nurses, pharmacists, and other team members, following the pathways’ protocols. KP HealthConnect facilitates the care pathways because it includes documentation templates, alerts, reminders, and other clinical-decision support capabilities. That is the power of KP HealthConnect—the ability to bring evidence to the point of care.

The Quarterly: What incentives do you give to physicians to encourage them to adhere to care pathways?

Hal Wolf: Permanente physicians have a culture of providing the best care for patients, and thus incentives are only one of many levers we use to improve care. Our physicians’ incomes are primarily salary based, but in some cases we use small financial incentives to reward quality performance. The strongest incentive is the performance data we share with our physicians. Performance data allow them to see the results of their actions and to identify ways in which they can further improve patient care.

The Quarterly: How do you handle booking and capacity management?

Hal Wolf: Members can schedule appointments in several ways: online, by telephoning a call center, or while talking to a physician. We try hard to make sure that same-day appointments are available when necessary. We have learned that it is crucially important that the booking system leave a certain number of slots open each day. Of course, we also assume that a certain number of cancellations will occur. Figuring out the right algorithm to ensure that the clinics are neither overbooked nor underbooked has taken time and effort. At KP, we use a central booking system in each region; we monitor utilization at each clinic and tweak our algorithms as necessary.

The Quarterly: Do all the clinics operate under the same governance and decision-making framework?

Hal Wolf: Our clinics operate in a similar way most of the time. That’s important, because patient care must be applied consistently to achieve good outcomes.

Yet we have to bear in mind that each clinic is slightly different from the others. After all, the clinics were built differently at different times, the physicians and nurses may have somewhat different capabilities, and the patient mixes may be different—one clinic, for example, may treat a lot of children, whereas another may have a high volume of elderly patients. We want to maximize the patient experience at each clinic, and thus it’s important that we not be too rigid about workflows and systems. The clinics have room for flexibility and innovation.

The Quarterly: How do you monitor performance?

Hal Wolf: The IT system is critical; without it, we would not be able to gauge the performance of our clinics and physicians or identify differences among them. For example, our IT system allows us to identify when a clinic has made a change to a care pathway and what results the change produced. If it enabled the clinic to lower costs while maintaining care quality or to hold costs steady while improving outcomes, we want to know about it; we may well want our other clinics to implement the change. A good IT system can also help us determine whether a change that increased costs was justified by the improved outcomes achieved.

The IT system also enables us to track physician performance on a regular basis. The physicians sit down as a group to pick the targets they want to achieve and the metrics that will be monitored. We then collect the data and share the results with them—each of them can see his or her performance. We periodically repeat the process of target and metric selection to ensure that our treatment approaches remain up to date.

Of course, physician performance cannot be assessed in isolation. For example, our best physicians tend to get the most complicated cases, but this means that they tend to see fewer patients, on average, than other physicians do. Our performance-management system has to take this into account. Also, physicians provide only one part of patient care, especially for people with chronic disease; nurses, pharmacists, and other clinicians are also involved. Usually, a wide range of information must be considered to determine why a specific outcome occurred. In Colorado, for example, we use balanced scorecards to gauge the performance of each department. These scorecards look at the care delivered by each team member, not just physicians. They also gauge member satisfaction, access, service, and more. The scorecards are developed with input from physicians, the other clinicians engaged in patient care, and the health plan—the payor side ofour organization.

The Quarterly: How do your physicians use the IT system?

Hal Wolf: KP HealthConnect enables our physicians to view a detailed history for each patient: when was the last time the patient had a checkup? What test results did she receive? How is she doing on her treatment regimen? All medical care is documented in KP HealthConnect. KP HealthConnect also flags problems. As an example, if patients fail to come in for scheduled appointments or to renew their prescriptions, the information is highlighted in the medical record.

The Quarterly: Have you been able to use the information in KP HealthConnect in other ways?

Hal Wolf: Our IT system was originally designed to provide information about individual patients, but our physicians quickly realized that real value could be derived from aggregating the patient data into disease registries. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes were among the first registries we created. Today, we have more than 50 registries. These registries enable all team members to determine how well their patients are doing in comparison with other KP patients, as well as how well their patients’ outcomes stack up against national and international benchmarks.

When we started these registries, we began by tracking outcomes and co-morbidities. Over time, however, the registries have grown more sophisticated. We can now determine how even small changes in care pathways can have a significant impact on outcomes, and we can study patients with specific combinations of co-morbidities to identify the best treatment approaches for them.

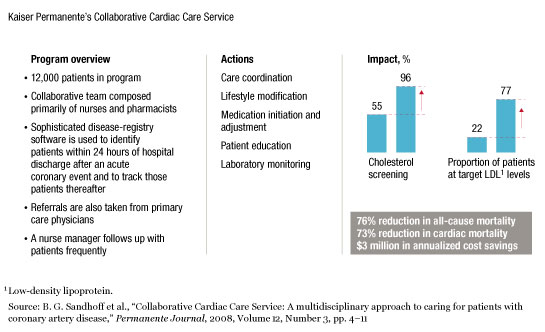

We also use the registries to help patients improve their health. In Colorado, for example, we have developed the Collaborative Cardiac Care Service for patients who have suffered acute coronary events (ACEs). As soon as these patients are hospitalized, they are identified and entered into the ACE registry and assigned a nurse manager. The patients are encouraged to participate in a wide range of follow-up services, including cardiac rehabilitation, exercise therapy, psychosocial support, and risk-factor modification—smoking cessation, for example. The nurse manager ensures that care is coordinated as the patients transition back to their homes, that they are taking their medications as prescribed, and that they undergo all appropriate follow-up tests. Responsibility for the patients is then transferred to clinical pharmacists, who follow them long term to monitor their therapy and adjust it as necessary. The results have been dramatic. The percentage of patients with LDL1 levels within the target range has more than tripled (exhibit). More important, the mortality rate has dropped by 76 percent.

Registering disease

The Quarterly: We’ve talked a lot about how physicians, nurses, and others interact with patients at KP. What role do patients themselves play?

Hal Wolf: The health of our members is our primary focus and our reason for being, and so the care experience we deliver is tailored to their needs. We also recognize that our services—even our best care pathways—will be unsuccessful unless our members take active responsibility for their own health. Thus, we have to build a strong relationship of trust with them. This is one of the reasons we work so hard to ensure that care delivery is seamless. We give our members electronic access to their health information and encourage them to consult their physicians via e-mail. We want to break down the barriers between patients and providers so that everyone is working together.

The Quarterly: What challenges is KP currently facing?

Hal Wolf: Like all health systems, KP faces a variety of challenges. One of our newestis how to cope with the vast amount of data we have collected about our members. Who should have access to this data? Who should be able to use it, and in what ways? As more and more information has been gathered, we’ve realized that the cost of maintaining the databases underlying KP HealthConnect has increased. We therefore have to prioritize which types of data access are most important. For example, it’s very expensive to make all data available in real time; perhaps some types of information can be archived and retrieved on an as-needed basis.

Like all health systems today, KP must focus on cost containment and efficiency improvements; we have constant discussions about the strategic needs of the organization and the investments required to support them. KP HealthConnect has enabled us to innovate in multiple areas of disease management. But we have to keep its costs under control.

The Quarterly: What advice do you have for other health systems that are thinking about creating more integrated care delivery models?

Hal Wolf: This is something we’ve been studying and talking to the National Health Service (NHS) about, and so I’ll offer a few suggestions.

First, the health system must establish an effective method for creating and implementing care pathways. As part of this effort, it must set up the right handoffs between the various providers and make certain that incentives are in place to support providers working together. The NHS, through its world-class commissioning program, is attempting to do just this.

Second, it is crucial that the health system think about how it collects and shares information. As it does this, the system must consider the needs of its constituents, such as its local providers, payor organizations, and national regulators. It must also make sure that its leaders are aligned on how and why information should be shared. We learned this lesson the hard way; developing a good IT system for a health system is a difficult task. Before we began using KP HealthConnect, we attempted to implement another approach to electronic medical records, and that implementation did not go well. We did not have focused leadership from the health plans or medical groups. That changed when George Halvorson became CEO of KP. The experience taught us that large-scale change can be achieved only if management is aligned on the same goals.

Third, the health system must determine whether its internal channels of communication are sufficiently open—and if they are not, open them. Communication is not necessarily a question of putting everyone involved in a patient’s care in the same building (although that certainly helps). Instead, it requires that everyone talk openly to each other and maintain the same patient-centric focus.

That last point may be the most important of all: the patient must always come first. We have found that the combination of a good data environment, strong end-to-end processes, clear communications, and a patient-centric focus creates integrated care. It also encourages everyone within the system to do their best.