In an organization with smart quality, quality control and assurance are embedded in the business processes and enabled by digital technologies (see sidebar, “‘Smart quality’ at a glance”). For instance, performance management of quality metrics across the organization may be digitally enabled so that virtually every employee has quality elements specific to their role incorporated into their responsibilities and daily work.

In a smart-quality organization, everyone owns quality. But there are challenges to overcome to reach that goal. In this paper, we describe how companies can get there.

Everyone owns quality

Most managers agree that every employee is responsible for quality. But typically, only the quality organization is accountable for quality in design, development, operations, and even postmarket activities. Sometimes responsibility extends to related functions, such as manufacturing science and technology, but even then, quality is not something for which everyone is answerable.

In fact, POBOS analysis finds that integrating quality activities into the day-to-day operations of every function that touches a product or quality process has a strong correlation with quality outcomes (Exhibit 1).1 Organizations that make quality everyone’s responsibility are also high performers.

Our assessment of quality outcomes and culture, based on a survey of 34 plants worldwide, shows that adopting a quality culture and capabilities is closely correlated with quality performance (Exhibit 2).

Accordingly, leading organizations are now driving cross-functional ownership of quality practices and outcomes. They are also developing quality practices and capabilities while striving to establish a culture of quality in every function. The larger goal is to drive greater ownership, participation, and execution to achieve high-quality outcomes.2

Challenges to building a quality culture

Most organizations understand the correlation of culture and capabilities with quality outcomes. Yet many still find it difficult to build and sustain them. In part, that’s because they treat quality- and compliance-related activities as necessary burdens for functions outside the quality organization. They focus on the direct organizational costs of ensuring good quality rather than on the costs and risks associated with poor quality. Both perspectives are important.

Moreover, traditional operations organizations treat quality-related activities as additional noncore efforts and often seek to comply with the minimum effort. This can be seen in many capability-building efforts where training sessions are more about checking the box than truly building quality capabilities.

Areas that need improving

To explore the underlying challenges of building and sustaining a quality culture and related capabilities, we conducted a series of quality-practices surveys. Our targeted study across more than 25 plants in Asia with 30,000 or more people shows the following five common areas for improvement (Exhibit 3):

- low recognition of quality-related achievements and often credit only for delivery targets

- inadequate problem-solving capabilities

- limited collaboration among functions to ensure high-quality outcomes

- weak acknowledgment of workers’ suggestions for improving quality

- insufficient dialogue and discussions with workers about quality metrics and performance

Many organizations address these issues with targeted improvement efforts. But to drive improvements in quality culture and capabilities, that is not enough, especially given the scale of change many organizations must undergo, across multiple functions and in short time frames.

In such situations, a better approach is enterprise-wide, assigning broad ownership of quality functions and initiatives to employees even beyond the quality organization while allowing quality functions to shift from policing to enabling other functions.

There are many critical areas of quality that an organization can focus on, for instance, recognizing quality practices and achievements and building problem-solving capabilities. It can also enable cross-functional collaboration in pursuit of quality excellence by, for example, assigning manufacturing and process-quality teams to ensure best practices on the shop floor.

How enterprises can embed smart-quality culture and capabilities

We call this approach pan-enterprise quality culture and capability building, a holistic approach focused on procedures rather than practices. It differs from traditional approaches in three ways:

- It addresses the entire organization, not just the quality team.

- It focuses on underlying mindsets and behaviors, not just quality systems and processes.

- It considers quality capabilities to be the cornerstone of enterprise-wide quality improvements.

This is a new way to build quality capabilities and shape the quality culture. It can help organizations establish new ways of working and operational models that develop and foster organization-wide quality.

The rewards of quality done right

Building a culture of quality is more than just a good idea. Organizations that have implemented smart quality across the enterprise have also achieved substantial performance improvements. Some examples include the following:

- A top-20 global generic pharma company wanted to achieve top-quartile patient outcomes, such as quality and delivery performance, but was reaching only the second and third quartiles. The organization undertook a holistic, culture-led transformation based on three initiatives:

- instituting a comprehensive shop floor and lab-management system to drive continuous quality improvements

- building problem-solving capabilities for more than 100 operations leaders

- promoting quality best practices for 2,000 employees, including operators and analysts, on topics that include good documentation practices, aseptic practices, and sanitization

Through this transformation, the company achieved global top-quartile results on selected quality metrics such as invalid out-of-specifications (OOS), a 70 percent reduction in deviations, and a 20 percent improvement in on-time in-full delivery. It achieved all this in just nine months.

- A top-ten Asian generics player suffered from poor quality performance, achieving only third- and fourth-quartile levels for most metrics. It was under intense regulatory scrutiny, receiving a warning letter and multiple 483 observations from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). To improve, the company undertook a pan-enterprise effort to build a quality culture that included training 10,000 employees in best practices for quality in critical areas such as cleaning and sanitization, problem solving, and materials movement. The initiative generated more than 4,500 quality-improvement ideas, of which more than 700 were implemented in the first six months. It also resulted in a 50 percent improvement in quality metrics, including for unconfirmed OOS and repeat deviations. The warning letter was lifted after 12 months, and there have been no subsequent 483 observations from FDA audits.

The three components of a smart-quality approach

To implement smart quality across the enterprise, successful organizations design and tailor approaches that match their unique cultures. While these approaches vary, they share three major phases.

1. Assessments of mindsets, behaviors, and capabilities

Organizations creating a quality culture typically start with a multifaceted assessment of their key practices to surface all the cultural and structural issues that pertain to quality excellence. Typically, this involves the following:

- benchmarking end-patient outcomes against global industry performance

- benchmarking quality practices against the industry, which can start with a structured survey of quality practices and visible behaviors, followed by a deep-dive assessment of underlying mindsets and behaviors. The assessment may include five-whys analyses based on focus-group discussions and in-depth, structured interviews.

- assessing the organization’s current capabilities can be done with best-practice self-assessments and structured evaluation tool kits

When carrying out these assessments, it’s important to surface insights at the unit level. While the overall architecture of the effort needs to be consistent across the organization, function- and unit-specific assessments are critical for customizing initiatives to address localized issues.

2. Pan-enterprise visioning

Top leaders can use the results of their assessment survey and their overall company strategy to establish a pan-enterprise vision that is shared and aligned across the organization. Visioning and aspiration-setting workshops can identify gaps between the desired end state and current performance levels. Senior cross-functional leaders can ensure the effectiveness of these workshops by participating and being aspirational; it’s better to fall short of a stretch goal than overdeliver on a modest one.

Leaders can help shape the solution by focusing on the future. The effort should not be a postmortem or criticize past actions, and ideas should not be rejected because they didn’t work last time.

3. Cultural and structural quality interventions

The third step is for leaders to jointly design and deploy cultural and structural interventions to deliver against the aligned goals, keeping the following principles in mind:

- Think of every employee as the learner at the center to ensure interventions are personalized, adaptive, and self-directed. Personalization might include optimized learning based on skill needs. Adaptive approaches often use algorithmic learning to modify learning based on an individual’s capabilities. And self-directed means that employees determine and lead their own learning journeys.

- Deploy all the interventions to each organizational unit, rather than select initiatives organization-wide and sequentially.

- Objectively measure progress, such as with leading-outcome metrics and indicators. If measures fall short, then make adjustments.

Using these principles, organizations can ensure greater and faster benefits, such as the following, than with more traditional approaches:

- Greater understanding and conviction. When an organization cascades a personalized change story, everyone responds differently. Some will recognize a need to change themselves, while others will connect to an organization-wide impetus. To build understanding and conviction, companies can use advanced analytics to explore micro-behaviors, such as attendance at daily huddles and pulse survey responses, and make tailored interventions, such as customized digital communications through online apps and platforms.

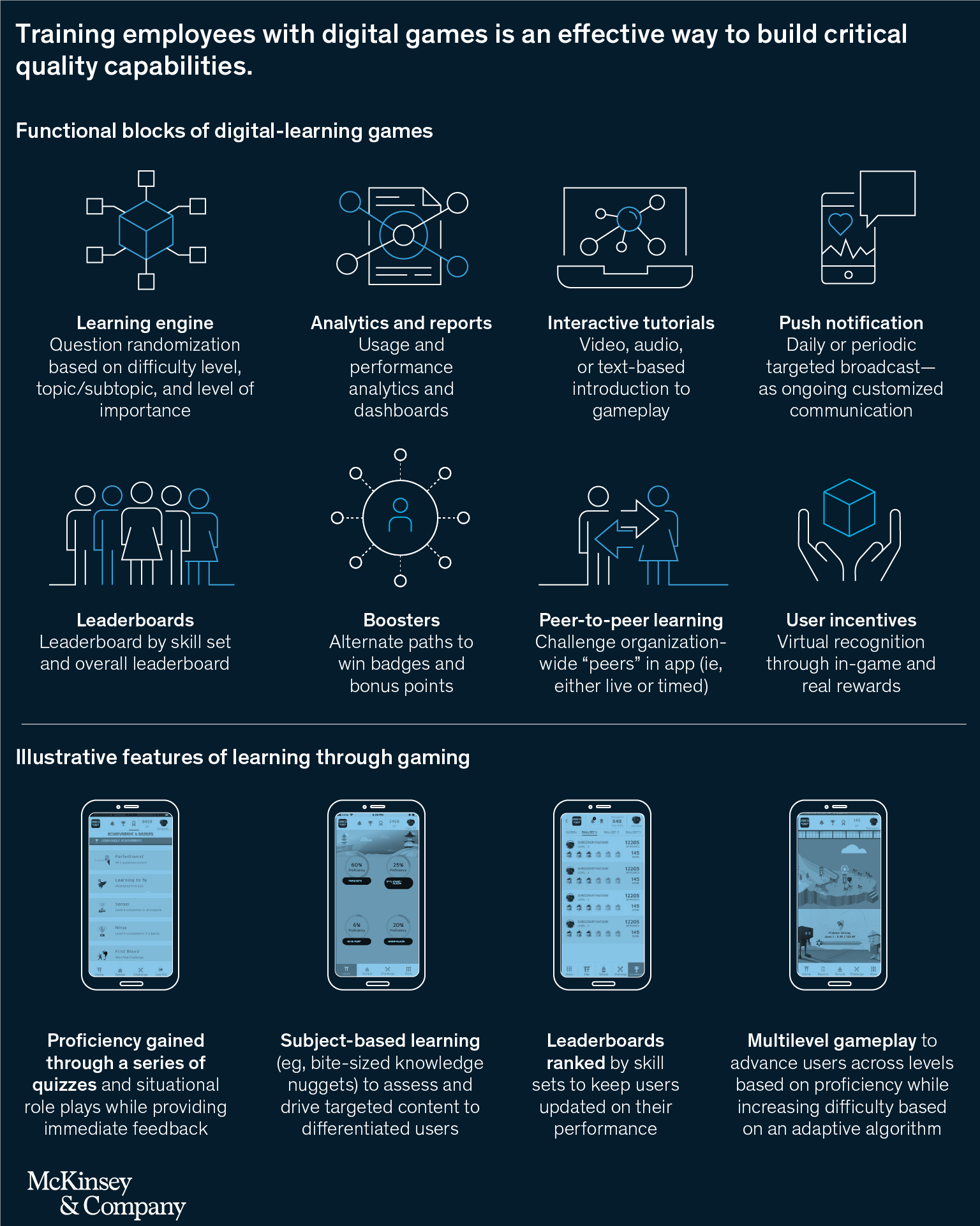

- Quality-capable employees. Employee capabilities can be built with digitally enabled interventions in areas such as problem-solving investigations. Learning on the go is a critical aspect of building quality capabilities in pharma and medical-device operations, where training exhaustion is common. Gamified learning, in which training content is presented in bite-sized challenges within a digital gaming experience, effectively builds critical capabilities (Exhibit 4).

- Strengthened cross-functional collaboration. For instance, leaders can jointly conduct factory floor walks, strengthening relationships and inspiring group leaders to collaborate.

- Streamlined processes and reinforcement. Agile cross-functional squads and circles are established alongside organization-wide quality recognition. Organizations that do this well often reconfigure their shop floor or lab-management systems to manage day-to-day issue resolution, prioritization, performance management, and governance. To do this effectively and efficiently, leading companies leverage digital quality management.

To ensure rapid, confident deployment, teams can best design, prototype, and refine these interventions with a series of pilots—for example, at two or three manufacturing sites—before scaling them up in subsequent sprints or waves.

A pan-enterprise approach to quality, focusing on quality culture and capabilities, can power the next S-curve in quality and a step-change in the overall performance of the pharma and medical-device sector.