Some companies have moved beyond merely coping with the crisis and are once again actively planning for the long term, according to a survey in the field from September 7th to the 11th.1 Over the past 12 months, the respondents to our economic conditions surveys have told us that their companies are cutting costs, reducing capital investments and headcounts, and making plans for weeks or months, not years—all in all, hunkering down to survive the worst economic shock in decades. Now, for the first time in a year, more respondents expect their companies’ profits to rise than fall in the near term. Product development and long-term planning are high priorities for many companies, and most are optimistic about their prospects in the longer term.

Overall, the responses indicate that a “new normal” is settling in—for many companies, an environment less comfortable than the one they knew in the pre-crisis world. Most are still cutting costs, and a third of all respondents say that their companies are in crisis. What’s more, executives remain skeptical about the economic health of their countries; a majority say that governments should continue supporting economies in the near term.

In the longer run, many executives expect the globalization of financial and other markets to resume after slowing notably in 2009. They also foresee additional significant changes in their industries and economies over the next five years, including a stronger government role in both. Nearly three-quarters of the executives expect their companies to be in a stronger position in five years than they were before the crisis. The executives also think that their industries will be more consolidated and innovative—but will grow more slowly.

The path to now

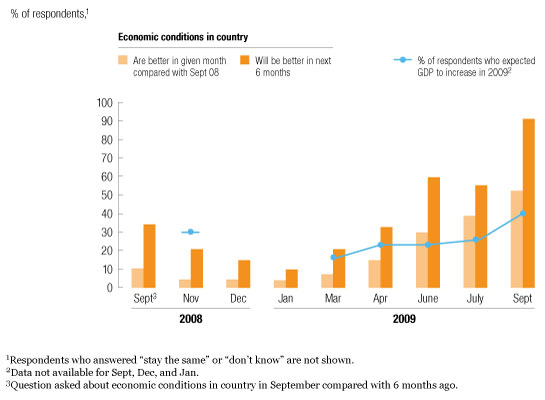

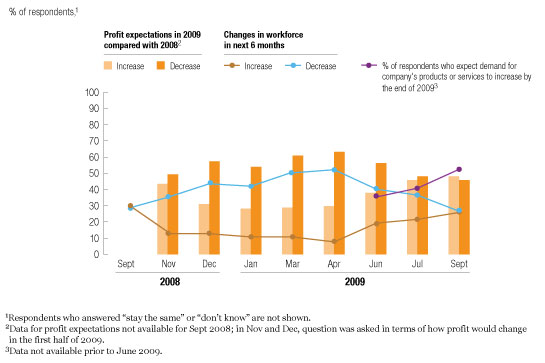

After reaching a nadir in January, the expectations of respondents for corporate profits and their national economies turned sharply higher in June (Exhibit 1; see also Exhibit 3). Since then, these expectations have risen strongly and consistently, in tandem with stock markets.

Differences in the hopefulness of executives are striking on the regional level, however. The crisis started in the United States, and executives in North America have consistently indicated that it will end sooner than executives elsewhere expect. Those in the eurozone have consistently been gloomiest about their economic situation and outlook.2 But the pattern for expectations is essentially the same in all regions, adding to the evidence from our surveys3 and many other sources that even the present crisis hasn’t fundamentally disconnected the world’s economies.

Economic outlook

Anxious hope for the future

Nineteen percent of respondents around the world—and 28 percent of those in Asia’s developed economies—say that an economic upturn has already begun. Each economic conditions survey since March has shown an increase in the hopes of executives for their national economies. As stock markets continued to climb over the summer, expectations for these economies rose quickly, too, though from a very low base. And in the past six weeks, expectations have risen markedly: 40 percent of the respondents now think GDP will rise in 2009 (compared with 26 percent six weeks ago), and 13 percent expect pre-September 2008 GDP levels to return in 2010.

But a majority of the executives don’t expect GDP to rise soon, and the responses also suggest other indicators of economic anxiety: 54 percent, for example, say that governments should scale back—but not stop—their support for economies. It’s particularly notable that this support for government action doesn’t vary by industry or by whether a respondent’s company is currently in crisis, indicating that the economic anxiety of executives goes beyond any immediate need for help for their own companies. This position is consistent with the executives’ overall positive views, reported in past surveys, of the role government has played so far in the crisis.4

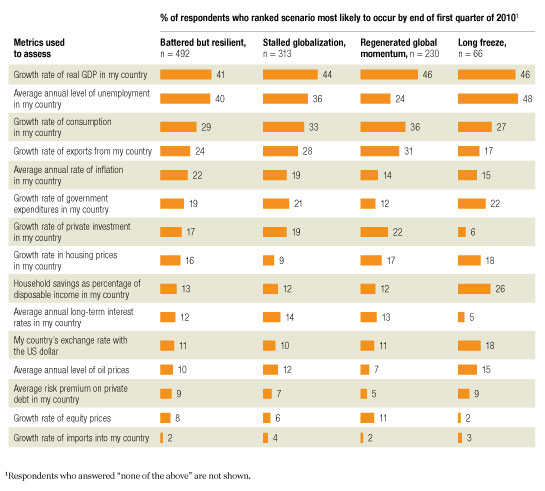

The anxiety of the executives is also highlighted by the fact that a plurality—42 percent—of them still think “battered but resilient” is the best description of the economy over the next several months. This finding suggests that the respondents expect a long, slow recovery. The next most frequently chosen description (31 percent) of the economy is even less hopeful: “stalled globalization.” Only 20 percent expect a fairly quick recovery. Executives say that their views are most influenced by the GDP growth rates of their countries. Beyond that, executives with different outlooks are influenced by very different indicators: those who foresee a quick recovery, for instance, are likelier to focus on consumption, others on unemployment (Exhibit 2).

Why executives expect what they do

Corporate priorities one year on

Many executives are nonetheless hopeful about their companies on several fronts. Expectations for profits are significantly brighter than they were six weeks ago, and expectations for customer demand are notably brighter. The share expecting that their companies will increase the size of the workforce over the next six months has risen to 26 percent, equaling—for the first time in a year—the share that expect it to decline (Exhibit 3).

Nearly two-thirds of all respondents say that their companies aren’t currently in crisis. But 45 percent of the respondents from manufacturers say that they are, compared, for example, with 28 percent of the respondents from financial-services companies. Respondents from manufacturers are likelier than those from companies in other industries—particularly service industries—to say that their companies are decreasing the size of the workforce and significantly less likely to expect a higher profit boost than respondents in any other industry. In the need to seek funding or the ability to get it, the differences between manufacturers and companies in other industries are minimal, and respondents from all industries have very similar expectations for their prospects five years from now. Manufacturers may just be recovering more slowly.

Profit, hiring, and demand outlook

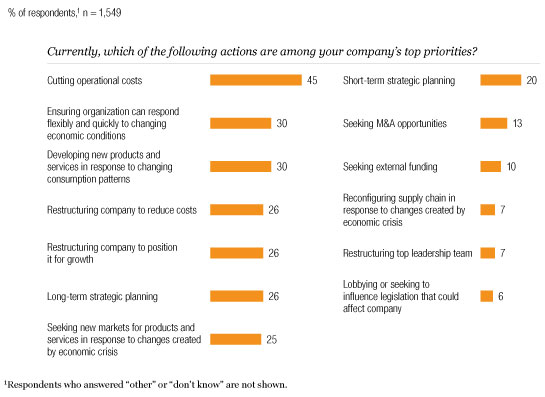

The top current priorities of companies are a mix of short- and long-term moves, including cutting costs, developing new products, and working to ensure that organizations are flexible enough to respond to changing economic conditions (Exhibit 4). Although three-quarters of the respondents’ companies are cutting costs and most will continue to do so, fewer than half identify cost cutting as a top priority. Equal shares report that their companies are restructuring to position themselves for growth and to reduce costs.

What matters most

The world in five years

Respondents from almost three-quarters of the companies expect them to be in a stronger competitive position five years from now than they were before September 2008. Respondents who expect their companies to be stronger in the long term are likelier than others to say that they are focusing on flexibility, new products, and long-term planning and that their industries will consolidate. One source of competitive advantage may therefore be the elimination of weaker competitors. These respondents are also likelier than others to expect their industries to become more innovative. Indeed, innovation as a response to the crisis is a consistent theme of this survey, and more than half of all respondents say that innovation is more important to growth than it was before the crisis. Interestingly, this is consistent with a finding from January, its low point, when executives said that governments could be most helpful to industries by supporting innovation.

More broadly, even though the crisis has slowed many trends related to globalization and raised many questions about the value of increasing economic integration, economies clearly are still more linked than not, and most respondents to this survey expect the links to increase—along with the role of government.

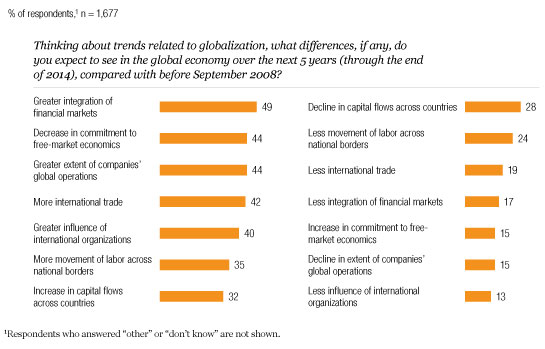

Executives are far more hopeful that globalization will intensify than they were at the low point of the crisis. Five years from now, a much larger share of executives expect more integrated financial markets and more extensive global operations and international trade than expect the opposite (Exhibit 5). Forty-nine percent of respondents now expect greater financial-market integration; when we asked a similar question, in March 2009, only 35 percent did.

Whither globalization

But these hopes are tempered too: there is no single area of globalization that a majority of executives expects will intensify. Furthermore, 44 percent believe that the commitment to free-market economics will be lower than it was before the crisis, though most expect little social or political backlash against the free-market system.

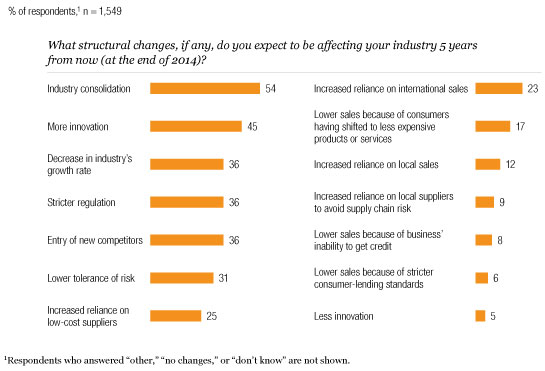

At the national level, majorities of executives expect that five years from now, governments will be more involved in the economy as a whole and that the financial sector will continue to see increased regulatory constraints. Just under half also expect tighter credit and a decreased rate of GDP growth. A slim majority of executives expect consolidation in their industries; many also foresee more extensive innovation and slower growth in their industries (Exhibit 6).

Long-term changes to industries

Looking ahead

-

Most companies are not in crisis: they’re managing in a new normal, with an enlarged role for government and lower long-term growth expectations.

-

Innovation is more important than ever; the companies that have the highest hopes for their own futures are likeliest to be focusing on it.

-

January was the month when executives expressed the direst views about the economy. They now look forward to economic growth, but few expect a quick, full recovery.

-

Executives indicate that the past year has slowed but not stopped globalization—and that skepticism about the value of free markets will continue as well.