The past two years haven’t been easy on children and teens. Their psychological well-being was already fraying prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it has worsened amid the pandemic’s social isolation and trauma.1 More than 200,000 children have lost a parent or in-home caregiver to COVID-19,2 and nearly three-quarters of US parents say the pandemic has taken a toll on their child’s mental health.3

But in order to help children and adolescents, their doctors also need support. Our recent survey found that more than 60 percent of pediatricians reported experiencing at least one dimension of burnout, a form of exhaustion resulting from excessive and prolonged emotional, physical, and mental stress (Exhibit 1). This condition can have a negative impact on the quality of care that doctors provide. According to one academic study on pediatric residents, doctors suffering from burnout were seven times more likely to make treatment errors, ten times more likely to ignore the social or personal impact of a child’s illness, and four times more likely to discharge a patient earlier than they should in an attempt to reduce their workload.4 Burnout can also cause pediatricians to want to leave the workforce.

Why pediatricians are experiencing burnout

To identify some of the major factors causing high levels of stress, fatigue, and apathy among pediatricians, we surveyed 451 doctors at children’s hospitals around the country (see sidebar, “Methodology”). Our findings offer insight into how employers—whether large or small health systems or independent practices—could lessen the load for these doctors, improve their workplaces, and ultimately retain these highly trained providers. In this article, we identify the unique needs of specific pediatrician groups, look at pediatricians’ career plans, and highlight the immediate steps organizations could take to continue meeting both patient and physician needs.

Women bear a disproportionate burden of the profession’s burnout

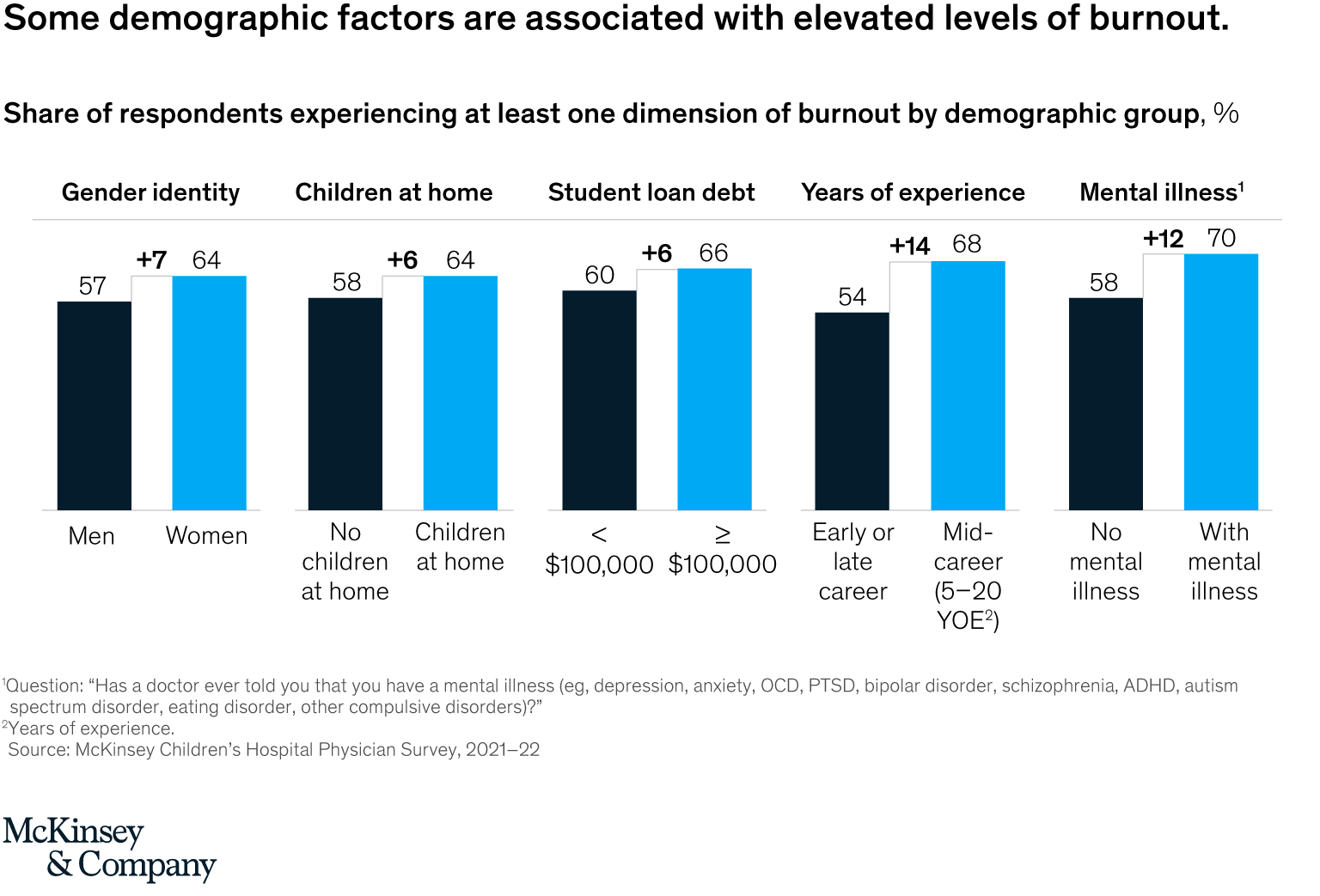

- Pediatricians who identify as female were more likely than their counterparts who identify as male to say they are experiencing burnout,5 a concerning finding given that 72 percent of all pediatricians are women.6 This greater susceptibility may be due to the fact that half of all women, regardless of their profession or work status, said they took on most or all of the additional pandemic-related responsibilities in their household, compared with 16 percent of men who did so (Exhibit 2).7

- But no matter their gender, pediatricians with children at home, with student loan debt, or who are midcareer also reported higher amounts of burnout than average.

Pediatricians with diagnosed mental illnesses may be more susceptible to burnout and attrition

- Pediatricians are no more likely than the general population to have a diagnosed mental illness or seek treatment for a mental illness. In both groups, the incidence is roughly 20 percent.8

- A majority (70 percent) of surveyed pediatricians with a diagnosed mental illness said they are experiencing at least one dimension of burnout. They were also twice as likely to say they intend to leave their position in the next year compared with pediatricians without a mental illness, at 30 percent and 15 percent, respectively (Exhibit 3).

One in five pediatricians plans to leave their job in the next year, and nearly half of those considering leaving in the next five years plan to leave medicine entirely

- Twenty percent of respondents said they are likely to leave their current position within the next year. This is lower than the 32 percent of registered nurses in the United States who say they may leave their current direct-care role.9

- Among those who said they are likely to change course in the next five years, half plan to leave the practice of medicine altogether to retire, pursue a different career path, or shift to a nonclinical job (Exhibit 4).

The majority of factors driving pediatricians to leave stem from workplace dissatisfaction

- Four of the top five reasons pediatricians gave for wanting to leave their jobs relate directly to working conditions, workloads, and organizational culture. A majority of respondents said they don’t feel listened to or supported at work, staffing levels are insufficient, and the workload is too intense (Exhibit 5).

There is a mismatch between the support pediatricians want from their employers and what they are getting

- Eight of the ten largest gaps between what pediatricians want and what employers provide relate to the working model and the organizational culture. Surveyed doctors said they want increased administrative support, flexible working hours, and more attention from leaders to their well-being and psychological safety (Exhibit 6).

- Our survey also found that employers may put too much effort into areas that have minimal impact on burnout, including employee resource groups, culture trainings, and technological support. Employers also tend to consistently underestimate how workplace elements are negatively affecting employee mental health and well-being, with another recent McKinsey survey showing an average gap of 22 percent between employer and employee perceptions.10

How employers can help

Supporting pediatricians is critical. If left unaddressed, burnout among these professionals may lead to an increased shortage of essential caregivers that could take years to resolve. To ensure that an ample workforce is available to support the optimal physical and mental well-being of children and families, employers can consider several actions:

- Recognize that burnout does not look the same in each physician. Employers can identify the drivers of burnout and regularly take the pulse of their physicians to monitor how these drivers vary over time.11 Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, for instance, incorporates a question about burnout in its “culture of safety” survey that all staff complete.12 This has helped the organization offer targeted support to people who need it. As part of its YOU Matter program, Nationwide Children’s Hospital uses more than 700 trained volunteer peer supporters to monitor staff and offer help following medical errors, traumatic situations, and patient deaths.13

- Understand that specific physician groups likely need targeted support. Parents and caregivers may need childcare options and flexible schedules,14 physicians with mental-health diagnoses may benefit from increased leadership attention and recognition for their accomplishments, and employers can create an inclusive environment for LGBTQ physicians to support their personal and professional well-being and advancement.

- Make wellness part of business as usual and clearly signal its importance from the top. When hospital leaders don’t promote or value well-being or mental-health initiatives, employees are less likely to find time in their busy schedules to take advantage of them. At Children’s Mercy, wellness services are treated much like continuing education, with employees using part of their shifts to participate.15 Hiring leaders to oversee the mental health of staff can also communicate gratitude and appreciation for frontline providers and staff. In July 2020, Children’s Hospital Colorado signaled the importance of staff health by hiring a medical director of provider well-being who is responsible for creating wellness programs.16

- Evaluate the workloads of physicians and reduce their burden. For example, employers can reallocate administrative tasks or conduct holistic reviews of how physicians are scheduled. Studies have shown that workplace flexibility plays a key role in reducing burnout among healthcare workers and has an impact on variables such as control over workload and perceived job stress.17

- Take a systemic approach. Although well-designed resilience programs are important and effective (for example, one study found that self-facilitated, small-group physician meetings reduced burnout rates by 13 percent),18 individual skills cannot compensate for unsupportive workplace environments. Employers can provide opportunities for physicians to help manage their stress and take steps to address overly demanding schedules or other elements that make workplaces unnecessarily taxing or toxic.

Just like their patients, pediatric-healthcare professionals need to be cared for and supported. Rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach to physician burnout, pediatric-health employers can look to the specific needs of their workforce in order to address overall pediatrician well-being and retention.