Although they may differ in structure or philosophy, health systems around the world have a common goal: to improve the health of the population they serve by delivering high-quality, accessible, and financially sustainable health care. Given ballooning health care costs and increasingly demanding consumers, achieving this goal is becoming ever more challenging. Quality, access, and sustainability form an elusive triad for most health systems, which struggle with at least one of these dimensions. For example, the United Kingdom has focused heavily on access and has succeeded in reducing wait times significantly, but now, more than ever, it needs to address sustainability as the government begins to squeeze public spending in light of the global financial climate. The United States, too, faces a daunting challenge in sustainability; its health care spending already accounts for more than 15 percent of GDP—yet the country still lacks universal coverage. Australia is focusing on quality and sustainability at the federal level, but in some of its states—Victoria, for one—access remains an important concern.

Effecting the whole-system change necessary to respond to these challenges is a difficult undertaking, but not an impossible one: some health systems are achieving considerable success by focusing on regional approaches to health care delivery. We begin this article by discussing three ways to define regional boundaries. We then describe a five-step process for developing a regional health strategy. Finally, we discuss what health systems need to do to implement their strategies successfully. Our thinking on these topics has been developed in part through our work in the United Kingdom but also draws heavily on our colleagues’ experiences in other countries.

What is a ‘regional’ approach?

There are a number of ways health systems can take a regional view. One is simply to follow existing geopolitical boundaries. London, for instance, has 1 regional strategic health authority, under which sit 31 separate payors, each covering an average of 240,000 people. In Sweden, all decisions relating to health care provision are made by the country’s 21 regional health authorities. Canada’s health care system is run by its 13 provinces and territories.

Another way to take a regional view is to follow the natural patient flows resulting from referral patterns (for example, from primary care to secondary care). In many areas, health care delivery is relatively self-contained—perhaps consisting of a major hospital, a few smaller ones, and several primary care providers. It is possible to identify the services provided within this “ecosystem,” analyze the end-to-end patient pathways used to deliver these services, and then pinpoint the levers that could be used to alter patient flows and rationalize capacity.

Third, a health system can define its regional boundaries by determining the optimal population base over which to design services. For example, there is strong clinical evidence that a minimum population of 2 million to 3 million is required to ensure sufficient volume to provide high-quality care in trauma services. In acute cardiac services, the minimum population size appears to be about 500,000. These and similar findings in other service lines support a regional approach to developing a health system strategy, irrespective of whether there is a formally defined geopolitical region. In fact, geopolitical boundaries often do not align with the optimal population base for the provision of high-quality services.

Five steps to a regional health system strategy

In essence, developing a regional health system strategy is an exercise in answering five questions: Why is change necessary? How will the needs of the population evolve? What clinical pathways will best meet patients’ future needs? What delivery models are needed to support optimal care? And, finally, are the proposed changes affordable and feasible?

A crucial component underlying the success of this approach is that it integrates clinical and financial perspectives, thereby avoiding the development of clinically based strategies that may be too expensive to implement or financially attractive strategies that do not clearly improve health and health care services.

1. Why is change necessary?

A regional health system strategy is more likely to gain and retain broad-based support if it clearly articulates a compelling “case for change”—that is, a rigorous assessment of the strengths and shortcomings of the status quo, along with a forward-looking view of the implications if change does not happen. Developing a case for change should be the first component of a strategy-formulation effort, as it forms the basis for engaging and aligning all relevant stakeholders.

In London, analysis revealed unacceptable variations in the quality and productivity of health services, as well as patients’ access to those services. In part, these variations are a consequence of the way the structure of health services has evolved: primary care and hospital-based care, for example, are not well integrated and thus cannot provide the seamless, proactive care management necessary to improve outcomes for patients with chronic diseases. In short, many patients do not have access to the right services in the right places or at the right times.

But a powerful case for change is not merely a well-crafted story; it must resonate with health care professionals, recognize their needs and concerns, and—most important—be underpinned by hard evidence. Clinicians will be dismissive of any approach that is not solidly grounded in facts. London’s case for change is based on established, well-respected sources of clinical data, such as peer-reviewed journal articles and independent reports by think tanks and regulators, and has been extensively tested and debated with clinicians (Exhibit 1).

London’s case for change

2. How will the needs of the population evolve?

Planning for sustainability requires an understanding of how and why future health requirements are likely to change. The second step in developing a regional health system strategy involves making projections of future clinical activity and describing how clinical practice and other trends will evolve, with a view to identifying the biggest challenges the system will face.

Popular belief holds that demographic and epidemiological factors, especially aging and the growing prevalence of chronic disease, are the primary drivers of demand for health system activity. We have found, however, that other factors—including changes in clinical practice, technology, the impact of health system and policy changes, and the public’s ever-rising expectations of health care—are also significant determinants of demand growth (Exhibit 2). For example, the rapid growth in cardiology throughout the developed world is driven more by angioplasty and other technological advances in care than by changes in the prevalence of heart disease. System and policy changes can have a significant impact on demand as well. In England, there has been an increase in emergency-room visits due to a combination of two factors: greatly reduced waiting times and a decline in the number of primary care practitioners providing care outside routine office hours.

What’s driving demand?

3. What pathways will meet patients’ future needs?

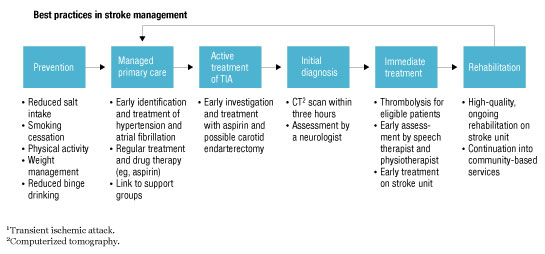

A cornerstone of a successful regional health system strategy is the redesign of clinical pathways to address the issues identified in the case for change and to meet the evolving needs of patients. Clinical pathways are evidence-based guidelines and best practices for achieving desired outcomes with optimal efficiency (Exhibit 3). Clinicians, health region leaders, and others work together to develop the pathways from end to end; as part of this process, they define the quality standards and protocols for specific pathways, the optimal flows through the system, and the process and outcome measures needed to track system quality. Because these discussions are framed around how to improve end-to-end patient care, clinicians are able to lay aside concerns about their own institutions and take a neutral, provider-agnostic view: they can focus not on where care is currently delivered but on where it should ideally be delivered.

An end-to-end clinical pathway

London chose to redesign high-level clinical pathways covering the entire spectrum of care—from the start to the close of life, and from prevention to complex tertiary services. For each pathway, a group of leading clinicians and other stakeholders met regularly to review the evidence base and develop recommendations. The groups sought the input of patients and the broader population through workshops. They looked at the provision and quality of existing services. The groups compared current practices to international benchmarks and case studies of best practice. They looked to Ontario, for example, for its experience with redesigning stroke services. They studied New Zealand’s models of midwife-led maternity care. For management of long-term conditions, they looked all around the world, from Berlin to California. By drawing on insights and best practices from health systems across the globe, the groups learned about novel approaches to delivering care, which challenged their traditional ways of thinking. Over the course of discussing optimal care pathways, the groups were also able to identify changes required to the way certain services were structured in London (for example, the city needed hyperacute stroke centers) and the enablers—such as workforce training and robust IT systems—necessary to ensure that the recommended pathways could be implemented.

Bringing clinical groups together to do this work can be challenging given the competing demands on clinicians’ time. We found it essential to provide the groups with adequate research and analytical support so that they can have insightful and productive discussions within a short time frame. Although organizing the groups and their regular meetings is no small logistical challenge, the result is a powerful force for change: clinicians who have played a key role in designing the future health system are dedicated to securing its delivery.

4. What delivery models are needed to support optimal care?

Implementing the recommendations made in each clinical pathway typically involves making changes in the way care is provided. The fourth step in developing a health system strategy is to outline what health care delivery organizations might look like, again drawing from innovative examples worldwide.

London adopted one simple maxim in developing delivery models: “decentralize where possible, centralize where necessary” (Exhibit 4).1 It is striking to note how many health systems across the world are implicitly applying this approach. In the United States, for example, there has been tremendous growth in ambulatory surgical centers—state-licensed, freestanding facilities that provide elective surgical care on an outpatient basis. The health system in Alberta, Canada, is exploring the transfer of certain comparatively routine services from hospitals to community and primary care providers. Stockholm is looking at collocating many tertiary services in a new hospital.

Reorganizing health care delivery

Why decentralize? First, decentralization results in better access, with people benefiting from the convenience of having core health services close to where they live. The goal is to provide a “one-stop shop” where initial consultation and diagnosis can happen in a single place and a single visit. Rooting services in primary care can also reduce unnecessary referrals, prevent overreliance on hospitals, and give primary care providers a more holistic view of patients’ health, thereby supporting and enabling prevention.

Why centralize? There is substantial clinical evidence that for certain complex conditions and procedures, specialization (for example, collocating specialist staff and services in facilities that see a high volume of cases) leads to better clinical outcomes and higher productivity. This evidence applies to routine planned care, such as joint-replacement surgery; to acute emergency care, such as primary angioplasty; and to highly specialized services, such as tertiary pediatrics.

For most health systems, “decentralize where possible, centralize where necessary” would entail the creation of a primary and community care infrastructure that is able to deliver integrated services close to patients’ homes; consolidation of a relatively small number of centers that perform complex procedures (those for which there is compelling clinical evidence that greater specialization improves outcomes); and the development of a new model for high-volume, less-complex inpatient care. London described six settings of care, which have since attracted interest from other regions in the developed world. The six are medical centers (also called “polyclinics”), local hospitals, elective centers, major acute hospitals, specialist hospitals, and homes.

Medical centers—modern multispecialty ambulatory facilities—are the linchpin of integrated care, especially for the proactive management of long-term conditions. These centers overcome the three main obstacles that have bedeviled many health systems that sought to shift care out of the hospital and into the community: a lack of access to diagnostics and other services, the small scale of most primary care practices, and the difficulty of integrating specialists providing outpatient services with primary care and diagnostics. By providing a wide range of services to populations of 50,000 to 80,000 (compared with the 3,000 to 4,000 people typically served by primary care practices), medical centers are able to meet most patients’ routine health care needs and act as a hub for home-based care. London has launched a citywide effort to get 150 medical centers up and running by 2017. Other providers that use similar delivery models include Kaiser Permanente, in the United States, and Polikum, in Berlin.2

Conditions that do not require specialist care but are not conducive to treatment outside of the hospital (for example, pneumonia in the elderly) can be treated in local hospitals, institutions that have all the necessary clinical infrastructure for routine care but not the cutting-edge technology and highly specialized services provided in major acute or specialist hospitals. Less-complex surgical interventions—routine cataract removal or hernia repair, for instance—can be performed in local elective centers, which focus on specific procedures and exclude emergency work to produce better outcomes and greater efficiency. At the other end of the spectrum are major acute hospitals and specialist hospitals, where highly skilled professionals with access to the best equipment and a clear understanding of the protocols for each condition administer the most complex types of care.

These delivery models will work effectively only if providers form strong networks. The Cleveland Clinic, in the United States, is a good example: it has developed hub-and-spoke models for the provision of elective care. Complex care is provided by specialists in hubs, which are closely linked to local services provided at facilities outside the hubs.

5. Are proposed changes affordable and feasible?

To ensure that the system will have the capacity and financing to implement the recommended changes successfully, it is important to understand the impact of shifting care from one setting to another—specifically, the financial and capacity implications by service line for each type of provider. This requires looking condition by condition—for example, at thelevel of the diagnosis-related group (DRG)/health care resource group (HRG)—at the optimal setting of care and describing what proportion of activity is likely to occur in, say, a major acute hospital versus a local hospital, in line with the recommendations made by the clinical groups.

For example, a clinical group in London determined that 70 percent of the mouth and throat operations that had been projected based on current volume could be performed in elective centers, while another 20 percent were more complex procedures (for instance, cleft palate repair) that should be done only in major acute or specialist hospitals. The group’s analysis also revealed that 10 percent of the projected demand consisted of procedures that, according to best-practice guidelines, did not usually need to be performed at all (such as tonsil removal) and therefore would not be undertaken in the new model.

Estimates of the cost of new service configurations can then be made and compared with potential future health care spending. In cases in which a novel delivery model is developed (for example, medical centers) and there is little data on the economics of provision, a comprehensive costing exercise is required. Such an exercise entails developing a detailed understanding of the day-to-day workings of the new model, including which types of patients would see which types of health care professionals, how much time they would spend, what consumables they would use, how much floor space would be needed, and so on.

Making change happen

Developing a strong health system strategy is important, but executing it is what truly matters. We have found that four elements are critical to success: an understanding of and a commitment to change, role models to champion the effort, formal mechanisms to reinforce change, and skills and capabilities for improvement (Exhibit 5).

Four components for achieving change

A compelling, fact-based case for change and a clear vision for the future help foster the necessary understanding and commitment. The reasons change is needed and the specific ways in which services will be transformed should be articulated so that they are as clear to the general public as they are to clinicians. To help build public support for the change and ensure that a wide range of perspectives is considered, many health systems have found it beneficial to involve the broader community as they develop the case for change. These people can also lend support to the clinician leaders, who will serve as the primary role models during the transformation.

The importance of the clinician leaders cannot be overstated, because they will be on the front line, working directly with other health care professionals while overseeing the strategy’s implementation. These leaders must be well-respected clinicians who are capable of gaining consensus from experienced colleagues, many of whom have strong and differing opinions on what the right answer is for patients. The example set by the clinician leaders will lend legitimacy and authority to the change effort and ensure that it remains independent from the self-interest of individual provider organizations. We have seen this approach work all over the world, from Hamburg and London to Ohio and Ontario.

Formal mechanisms—from performance review processes to financial incentives—must also reinforce the change effort. By continuously monitoring providers’ performance with regard to quality, access, and patient experience, health systems can track progress and intervene with poor performers as necessary. And by publicizing comparative performance metrics, health systems can help patients make informed choices among providers. Performance transparency can also create peer pressure to do better; in Bristol, England, transparency about cardiac outcomes led local providers to achieve sustained improvements in the quality of care delivered. Equally important are organizational and individual incentives for staff members. Promotions, for instance, must be based not on length of service but on objective performance evaluations. Given the power of financial and professional incentives, it is critical that the right things—that is, the most important determinants of quality—are encouraged.

Finally, all stakeholders—payor and health system managers as well as the health care workforce—must be equipped with the skills and tools needed to think and work in new ways. Recognizing this, the regional health authority in London has launched a large-scale program that seeks to enhance local payors’ understanding of clinical best practices and enable them to make smart management decisions. It also undertook a comprehensive review of its workforce and health care educational offerings to ensure that it will have the right number of appropriately skilled staff to achieve its ambitions. Based on this review, London has dedicated funds specifically to address gaps in supply (for example, it will train additional emergency nurse practitioners to support improvements in the urgent care pathway) and to develop and train future clinician leaders.

One of the most important tools that all stakeholders will need is a good IT system, and thus it is crucial that the health system understand and address the technological requirements that a change in its service model will entail. For example, shifting imaging services from the hospital to the community setting requires telemedicine for remote reporting. Reliable and user-friendly information systems are essential both for monitoring performance and for delivering high-quality care.

The ultimate impact of a health system redesign should be transformational improvements in the health and well-being of an entire population. In London, we expect significant quality improvements as well as efficiency benefits exceeding £1 billion. Ontario, by improving stroke care, has been able to reduce readmission rates by 16 percent per year and the 30-day mortality rate by 8 percent. By taking a regional approach to strategy development and implementation, health systems worldwide can achieve positive change and make a real difference in the lives of the many people they serve.